This morning Rod and I both woke early to watch the broadcast of the Collingwood vs Adelaide game live on laptop computers in our respective rooms. We watched the game from the first bounce, which was at 4.20am Manchester time. Collingwood won, which set the tone for a good day ahead. We left after an early breakfast and headed for York, just over 70 miles (about 115 km) away. For much of this distance, traffic on the motorway moved fast, and we arrived in just under an hour and a half. Rod and I had tickets to visit the York Cold War Bunker at 11am. Marg and Cornelia were not interested in that, so Rod drove us through York and dropped Marg and Cornelia off near the Minster. They spent the next hour and a half enjoying the town and checking out the shops. Marg bought some wool, as she often does when she visits a new town. Marg and I have been to York before, and even stayed overnight here, but today all of our planned visits were new to us.

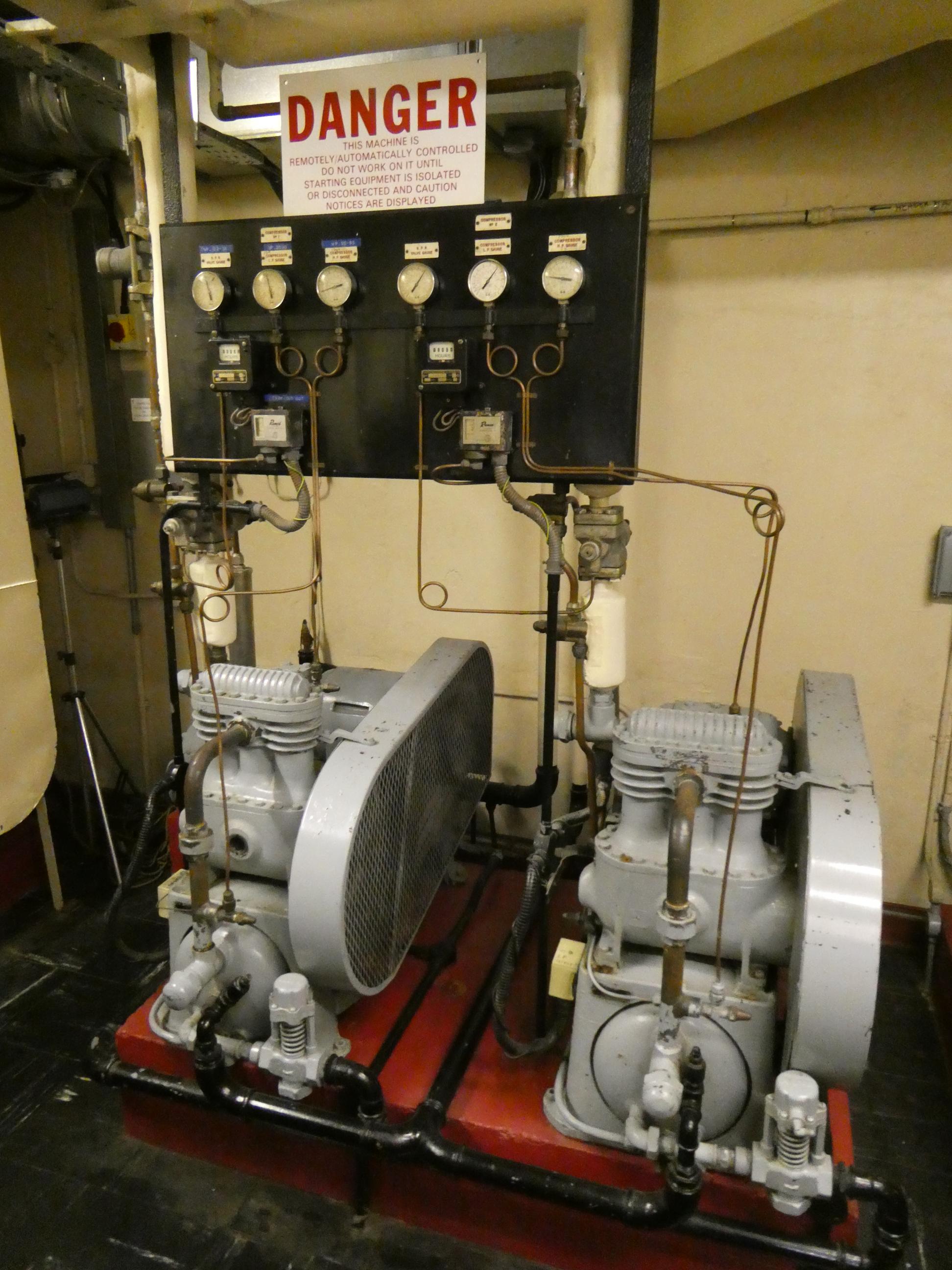

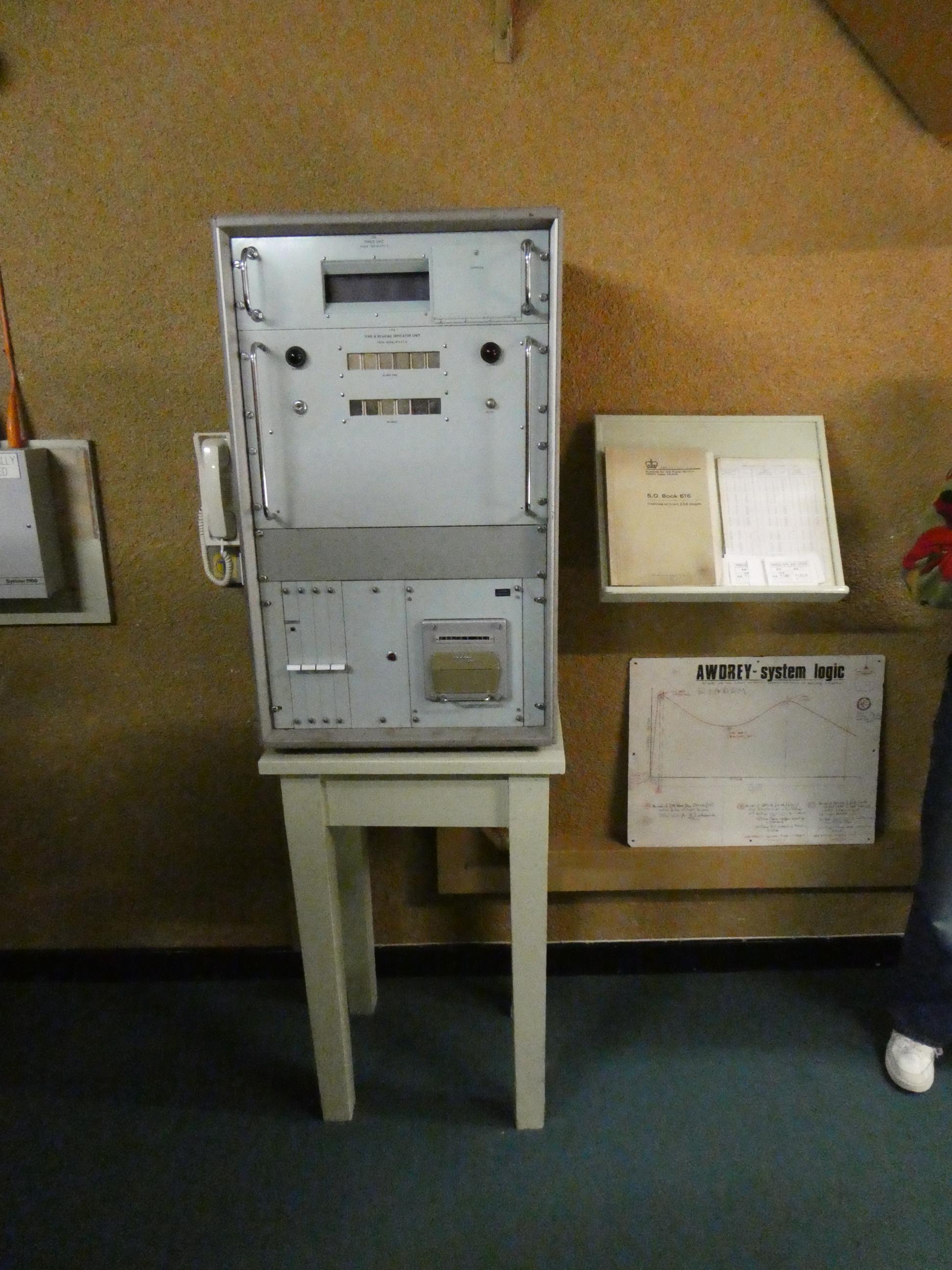

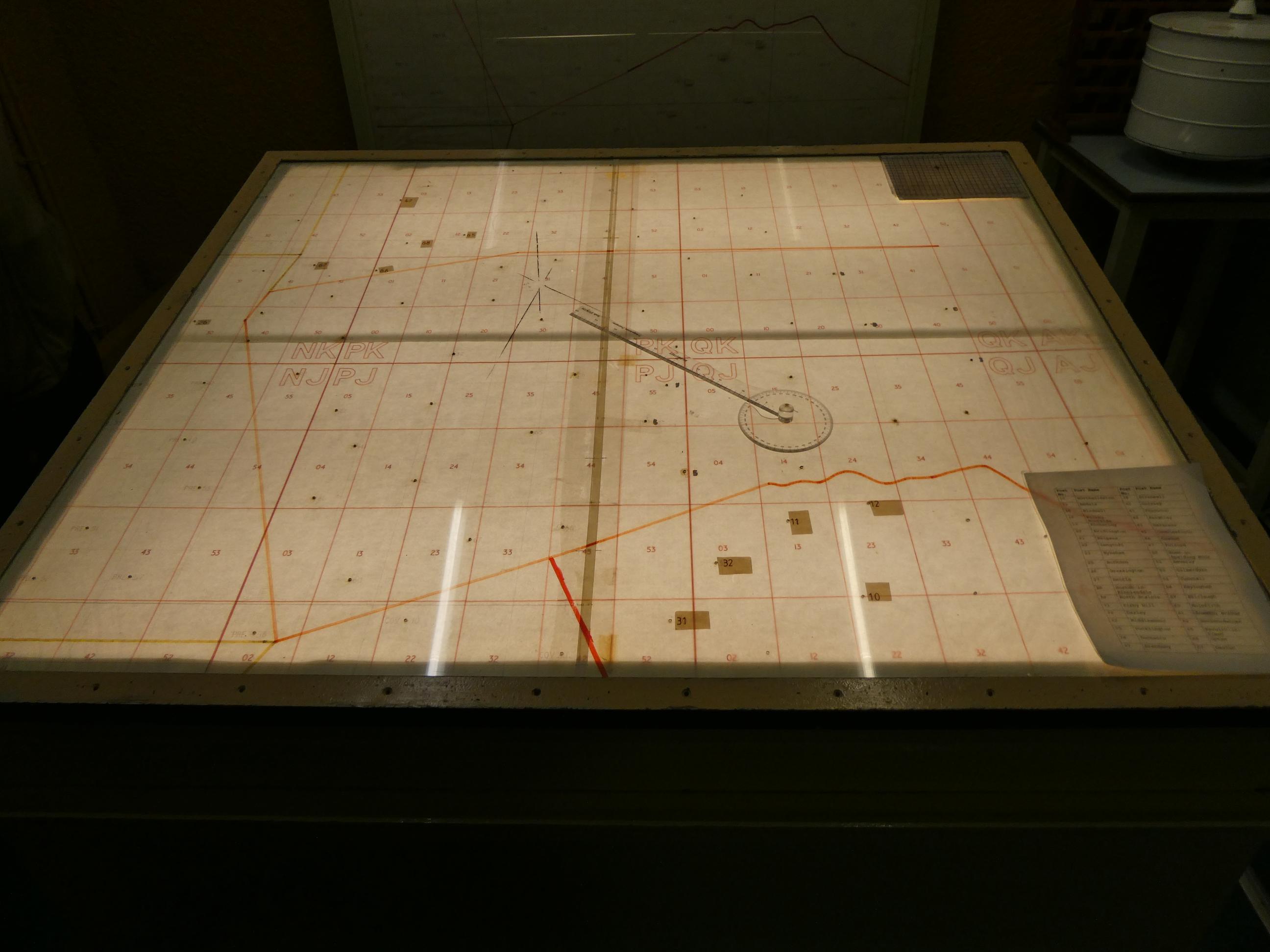

The York Cold War Bunker is in a suburban area of York, surrounded by public housing. It’s a remnant from the Cold War, and operated between 1961, when the Berlin Wall was built, and 1991, not long after the Wall came down. At times during that 30-year period, Britain felt particularly vulnerable to a nuclear attack from the Soviets. It feared a nuclear strike could devastate one of its cities, causing tens of thousands of civilian casualties, wiping out buildings and public infrastructure, and laying a carpet of deadly radiation that could contaminate the soil, water, crops and fields that fed the people of Britain, and inflict death or serious illness upon many thousands of civilians. One part of England’s defence against such an attack was to build about 30 bunkers, such as the one in York, located around the country. The role of these bunkers was to monitor any nuclear explosions that occurred in their vicinity and track the radioactive fallout. This information was to be collated and shared with other bunkers in different regions, as well as with the government, military and other authorities. The information could then form the basis of warnings and advice for the public about how they should respond in the event of a nuclear attack. The bunker was manned only by volunteers of the Royal Observer Corps for the thirty years it was operational. Soon after the Cold War ended, the ROC unit was disbanded and the bunker was closed up and abandoned. Very little funding was made available to the ROC, so many of the facilities available for the volunteers were quite rudimentary. In the event of a nuclear explosion nearby, up to sixty volunteers might have had to remain in the bunker for a period of thirty days, monitoring every detail linked to the attack and informing the people who needed to know so that they could manage a response. Some duties would have required some of them to venture outside, where radiation levels might be highly dangerous, wearing only the overalls they were issued as protective clothing. The plant room controlled power, water and air supply. The operations room was the nerve centre, where all incoming information about bomb attacks would be plotted on a large map of England that included classified information such as the location of airfields and military sites. Thankfully, the Soviets never launched a nuclear attack on England and the bunker’s volunteers never saw any action. One wonders if any of their efforts would have been effective against a nuclear strike anyway. York City Council had plans to dismantle the building and sell off the land, but thankfully one councillor thought it had heritage value, and convinced others to vote against destroying it. It took six years for a group of dedicated enthusiasts to clean it up before it could be opened up to the public.

Rod drove back into central York and found a car park. We walked along the busy Shambles to York Minster, where Marg and Cornelia were waiting. They’d had a great time while we were in the bunker and, like us, were a bit hungry. We had timed tickets for the Minster that prevented us from having lunch beforehand, but we managed to squeeze in time for an ice cream. On such a beautiful day, why not? York Minster is one of the largest cathedrals in all of Britain. It began as a Roman Catholic cathedral, but is now an Anglican one, following Henry VIII’s decision to break away from Rome and become head of a new church, the Church of England. The Minster’s Archbishop is responsible for overseeing the ministry of the Anglican Church north of the River Trent, and is England’s second most senior bishop, behind the Archbishop of Canterbury. The last time Marg and I were in York, the Minster was closed to visitors because a training session for novice priests was taking place, so we were looking forward to finally stepping inside. Rod and I took advantage of a free guided tour, which not only covered the history of the Minster and the various churches that preceded it, but also outlined the stories behind the design challenges, construction techniques and craftsmanship that contributed to the building of this magnificent structure. Over the years tragic fires have caused considerable damage. One occurred in the quire after a man troubled by his past hid in the Minster after Evensong, made a pile of combustible materials, and set fire to it. As a consequence, today’s replacement quire dates from the Victorian era.

We stepped out into the busy streets of York. It seems lots of people decided to get out and about in the sunshine on this beautiful day. The Shambles is narrow and was particularly crowded. We found a place to eat that was probably hundreds of years old. They sent us upstairs. We ducked our heads on the rickety staircase, so as not to bang them on a beam. Up there, the floor sloped and the tables had an even greater slope, to the point where we wondered if our coffee cups might slide down the table top and fall onto the floor. It was hard to tell whether the building was originally built that way or whether wear and tear over the centuries had caused it to be this way. At the end of The Shambles was Whip-Ma-Whop-Ma-Gate, supposedly the shortest street in all of England.

Clifford’s Tower was not far away. It was once part of York Castle. My fourth great grandfather John Allen was once briefly imprisoned in another part of the castle for a short time before he was transported to New South Wales after being convicted of horse theft. Clifford’s Tower is essentially the ruined keep of the castle. It stands alone on the top of a hill. Clifford’s Tower was originally built out of wood by William the Conqueror, but was rebuilt in the twelfth century using limestone – this is the same structure we visited today. The Tower and its occupants were involved during the English Civil War, as well as during the Reformation, when Henry VIII led a breakaway from the Church of Rome. We walked up the steep steps. There’s not a great deal to see inside Clifford’s Tower these days, but further steep, winding steps will take you up to the too of the battlements. From there, you can see all over York.

We drove back to Manchester late in the afternoon. The sun was getting lower in the sky and we were often looking into the bright sun. Just like we experienced in York, hundreds of people were out and about in Manchester, many of them with a drink in hand and having lots of fun. There are a few bucks’ and hens’ nights in town tonight, leading to a beer wagon full of women circling the streets, and mobs of men and women in a range of different costumes parading up and down the street and making a hell of a lot of noise. There’s also a free jazz festival going on here. Manchester is buzzing, and tomorrow it may buzz even stronger, as the annual fun run is taking place. The starting point is just around the corner, a two-minute walk from our hotel, and even our street is due to be closed to all traffic from about 3am. Somehow we’ll have to make our way through the crowds, wheeling suitcases, meet up with Rod in the car, and try to find a street or road that’s not closed to traffic and will lead us out of town.

Awesome day and awesome win for the Pies too. X

LikeLiked by 1 person