Today we’d booked a private day tour of South Mainland with James Tait from Island Trails. James picked us up at 9.30 am and pointed to the guy in the yellow jacket standing by the LOC sign which had recently been placed there. He pointed out that LOC indicated location shooting for the new episodes of the Shetland TV series and that the security guy was there to keep people away when the cameras were rolling. A short time later the film crew’s vans passed us on their way to the site. Jimmy Perez’s house is less than 100 metres from the LOC sign, although Jimmy has left the show for this series and been replaced by Ashley Jensen (from AfterLife) who plays DI Ruth Calder in Season Nine. Five minutes later James stopped the car in front of Duncan’s house from the show. Duncan is the biological father of Jimmy’s step-daughter Cassie in the show. You can probably guess that I’m a big fan of the show. James assured us that Shetland really doesn’t have as many murders as you see on the show, although he did tell us that there was a drug related murder here a year or two back.

Duncan’s house, which is a real house with real occupants (so is Jimmy’s) is in a relatively new housing development overlooking Lerwick. It has been build to resemble housing in Norway, which is not so unusual, as Shetland belonged to Norway until 1468. Many Shetlanders have Norse heritage. Many place names are from the Norse language, and quite a few people here still speak a dialect called Norn, which has its roots in the Norse language.

Heading south, we stopped at Fladdabister to look at some croft houses. Crofts were small stone cottages attached to a piece of land. They were owned by wealthy lairds (landlords), who also owned stores where goods like wool, meat, fish, knitted goods etc could be exchanged. Because the crofters were tenants on the laird’s land and they owed rent, the laird required them to work for him and provide goods for his stores, and he also required them to access goods only from his stores. Rather than pay the crofters with money for their labour, the laird kept entries in a ledger. One column was what he owed them, and the other was what they owed him. Needless to say, crofters were always in debt to the lairds. It was a form of enforced slavery. Life as a crofter must have been incredibly challenging. This croft house in the photos was two storeys once, but the second storey flooring and beams, which were probably made from driftwood have rotted and disappeared long ago. You can see that there are fireplaces for each level.

Just past Fladdabister we stopped to look at the island of Mousa. No one lives on Mousa anymore, but people lived there during the Iron Age, about 2,500 years ago. They constructed a very large tower, known as Mousa Broch, out of stone. It stands 13 metres tall, and if you click on the second photo below to enlarge it, you will be able to see the broch in the centre of the photo, near the shoreline. A broch is like a large roundhouse where the people could shelter and stay relatively safe from attackers.

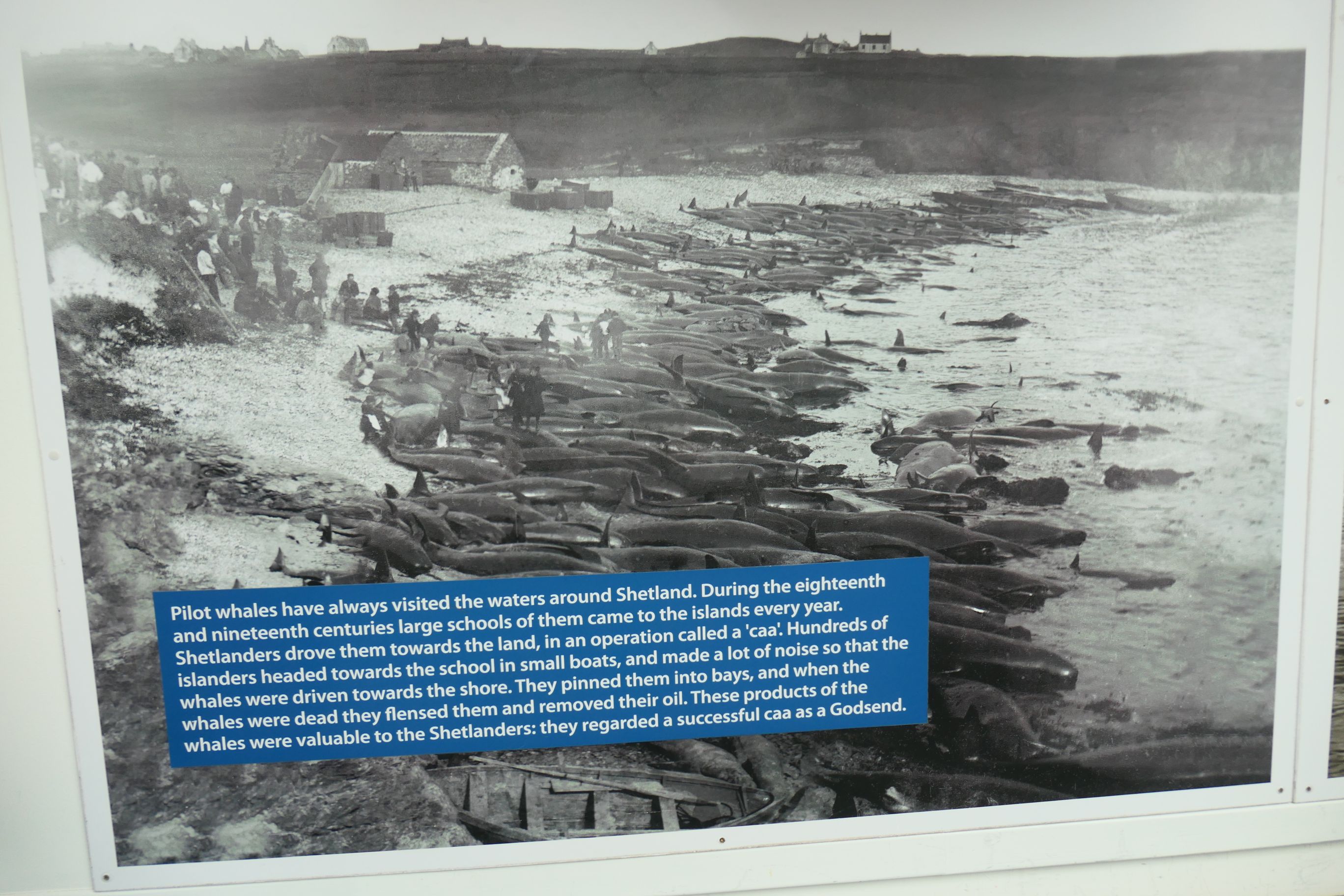

We stopped at Hoswick to about a famous event during the 1800s that brought an end to the unjust system of wealthy lairds forcing poor crofters into servitude. When pilot whales entered the voe (bay or inlet), the people used to go out in boats and herd them in to the shore. The whales would beach themselves, and the crofters would then slaughter the whales for valuable by-products such as blubber, oil, whalebone etc. The lairds used to demand one third of all revenue from the whale beachings, but the crofters argued that the lairds had no right to claim any revenue at all. The case was tested in two courts and the judgment in both cases went in the crofters’ favour. These rulings broke the power of the lairds forever, and from that time on crofters who worked hard could use the proceeds to improve their lives. The photo of the beached whales is from the same beach as the one in my photo below. A little further round the coast, James pointed out a family of shelducks.

Our next stop was the Crofthouse Museum at Dunrossness. This is an actual crofthouse, built around the late 1800s. It has been constructed of stone, driftwood and thatch made from oat straw. Inside the crofthouse, visitors will see typical furniture that crofters would have used, such as box beds for adults and older children and cradles for infants. Other implements used by crofters were also on display. When we stepped inside, peat was burning in the fireplace and a peaty, smoky smell pervaded the dwelling. This is a hands-on museum. Steve, the genial custodian who was on duty today, was happy for us to touch and feel the original items on display, which doesn’t happen in many museums I’ve visited. Attached to one end of the museum was a cattle byre, where livestock could be housed during the harsh winter. There was also a form of shed, where grain could be threshed and milled by hand, then dried by a kiln.

Approaching Sumburgh Head Lighthouse, the road actually crossed one of the runways at Sumburgh Airport. The single track road climbed sharply to the lighthouse, which was designed by Robert Stevenson. He was the grandfather of Robert Louis Stevenson, author of Treasure Island and Kidnapped. Stevenson’s lighthouses are rightfully famous as some of the finest examples of 19th century Scottish engineering knowhow and skill. The lighthouse has been operating for over 200 years now, keeping mariners safe as they approach Shetland. For most of that time it was the responsibility of a lighthouse keeper to keep the lamps burning, but today the light is operated automatically. A huge rotating lens flashes light three times every 30 seconds. The light can be seen almost 40 km out to sea. The lighthouse has also featured in episodes of Shetland.

The highlight of the visit to Sumburgh Head for us today was another chance to see puffins up close. They have made their nests on the rocky cliff faces surrounding the lighthouse. Fulmars are also there, as are other seabirds. We really focused on the puffins today, not only because we love the way they look and their antics, but also because they are the most accessible. They do not appear to be at all frightened by humans, so I was able to get very close to photograph the puffins, whereas the fulmars kept their distance. James, our guide, was delighted to spot a puffin with a beak full of sand eels. He spoke to a ranger, who confirmed that this was one of the first sightings of feeding puffins this year. James said that from now on it would become more common to see puffins with fish in their beaks. I photographed a few with pieces of plants in their beaks. I guess they were using the plants to make their nests.

We had lunch at the Sumburgh Hotel, then walked next door to the Jarlshof archaeological site. What is remarkable about this site is that, as you walk around it, you walk through about 4000 years of human history, all in one place. The first ruins we saw were those of an oval shaped house, built by Neolithic people about 4000 years ago – the same people who built Skara Brae on Orkney, and roughly about the same time. As James walked us around the site, we moved from Neolithic to Bronze Age to Iron Age. The Bronze Age people lived in small roundhouses, and the Iron Age people built larger wheelhouses and a massive broch. Parts of the broch have disappeared as the coastline beneath it has gradually eroded, taking the stones with it. Picts were also here towards the end of the Iron Age. Situated immediately alongside these ruins, are those left by the Norse people between the 9th and 14th centuries. They had come here to farm, rather than to rape and pillage. Today you can still see the long, rectangular shape of the longhouse. The final structure on the site is the Jarlshof, or Earl’s House, built in the 1500s and once home to Earl Patrick Stewart. He was a tyrant who ruled Shetland and Orkney with an iron fist, causing great hardship to the people of those islands. In time, he was executed for treason.

James took us on a scenic drive past his mother’s childhood home at Dunrossness, where he stopped and went into the field with a pair of binoculars to count his ewes. As well as a tour guide (an outstanding one, I might add), James is a crofter. When he had counted all thirty of his ewes, well satisfied, he returned to the vehicle and we continued on our way. I couldn’t help but reflect on the amazing view his mother must have had, over to the freshwater loch, from her window when she was growing up.

Near Quendale we passed a beautiful sandy, sheltered beach. We stopped the car and looked a little closer. Resting along the water’s edge were a number of harbour seals. The scenery just seemed to be getting better and better. With the sun out and blue skies, we couldn’t have picked a better day to see Shetland in all its glory. South Mainland has beautiful views around just about every corner.

Our final stop of the tour was the sandy tombolo (a narrow sand bar that connects an island to mainland) that joins St Ninian’s Isle to the mainland. No one lives on St Ninian’s Isle any more, though the farmer who owns it still grazes his sheep there. In 1958, a buried hoard of 1200 year-old century silver jewellery was discovered on the isle. It was buried beneath a stone slab in a very ancient chapel. People believe the monks may have buried the hoard here so it would not be stolen by invaders.

James dropped us off at our lodgings in Lerwick at about 5.30 pm. It had been another fulfilling day. We went back to the local steakhouse for dinner – the same place we’d dined at the previous night.

Such a beautiful place! Puffins, puffins and more puffins!! Your pictures and descriptions are fantastic Garry! Keep having fun! X

LikeLiked by 1 person