As I mentioned in yesterday’s blog post, we stayed overnight in a city in Northern Ireland that goes by two different names. Londonderry is the name used by British loyalists and Derry is the name used by Irish republicans, the people who want the British to leave Northern Ireland so that its counties may unite to form an Irish republic with the counties of the Irish Free State. Essentially the loyalists are the protestant community and the republicans are the catholic community. For the remainder of this post I am going to refer to the city as Derry.

This morning we took a short walk from our hotel to the part of Derry known as Bogside. Bogside is just outside the city wall, and is a predominantly catholic community which is staunchly republican. For many years Bogside has been a working class neighbourhood. Its name comes from the fact that the land it lies on was once marshland created when the River Foyle’s course was diverted. Bogside became a focal point for violence during the terrible period of recent Northern Irish history known as The Troubles.

During the 1960s, the catholic community of Bogside was oppressed. Despite being the majority of the population, they did not have a majority of elected officials on the local council, as the controlling loyalists had altered electoral boundaries to ensure they remained in control, despite their fewer numbers of voters. Secondly, only land owners were entitled to vote in council elections. Poorer people, such as those in Bogside, who paid rent could not vote. The loyalists who ran the council controlled public housing, and limited the amount that was available to catholics, limiting their living area to only one small part of Derry. Additionally, many of the loyalist business owners and employers in Derry gave preference to protestants applying for jobs ahead of catholics. Naturally, this oppression led to great unrest in the Bogside republican community. Activists among them began agitating for a fairer deal. In 1968 a protest march was organised. Officials banned the march, but it went ahead anyway, led by some British Labour politicians. The police of the Royal Ulster Constabulary were brought in to quell the marchers, and assaulted some of them with batons. When footage of the police violence was broadcast on news bulletins, support rallied for the marchers. Further marches followed, with the Bogside catholic community showing solidarity in demanding their civil rights. As unrest escalated, some police broke into Bogside homes and assaulted the residents. In response, the Bogside community erected barricades and initiated patrols to prevent police from entering their neighbourhood. On a wall, an activist painted “You are now entering Free Derry.” That wall has never been pulled down and its prominent in Bogside today. After further clashes, police action led to the deaths of several Bogside republicans. In August 1969, when a protestant march passed close by Bogside, catholics hurled stones at them. A battle between catholics and protestants soon ensued. Police tore down the barricades and protestants surged into Bogside, damaging catholic homes. Petrol bombs were thrown. The rioting lasted several days and became known as the Battle of the Bogside. For the first time in the escalating conflict, British troops were flown in. Over a thousand people were injured in the fighting, although no deaths were recorded. Soon violence flared in other parts of Northern Ireland, as republicans clashed with police. In Belfast, police and loyalists stormed catholic communities, leading to killings and the destruction of whole streets. Back in Derry, police and the military were unable to enter the Bogside neighbourhood, where the IRA had become active. In 1972, a civil rights march in Bogside soon became a bloodbath. It has gone down in history as Bloody Sunday. British soldiers shot 26 unarmed civilians, killing 14 of them. Some were shot while running away, others while they tried to help the fallen. Many others were injured by action from the soldiers. Bloody Sunday was one of the most tragic incidents of the entire thirty year period of The Troubles. Please note that this is a very brief overview of a very complex period of history as I understand it.

This morning we viewed many of the Bogside Murals that adorn the walls of houses in the neighbourhood. They are powerful murals with a pointed message. They depict the violence of Bloody Sunday and the Battle of Bogside and they show the heroes who led the fight for civil rights. Some depict the innocent people who died in the conflict. Although some of the housing has replaced what was here 50 years ago, it’s clear that this is still a working class area. Irish flags fly proudly. It’s quite evident where the loyalties of the catholic community of Bogside remain to this day. You can’t help but be moved as you walk along these streets, especially if you empathise with the people who were the innocent victims caught up in the violence.

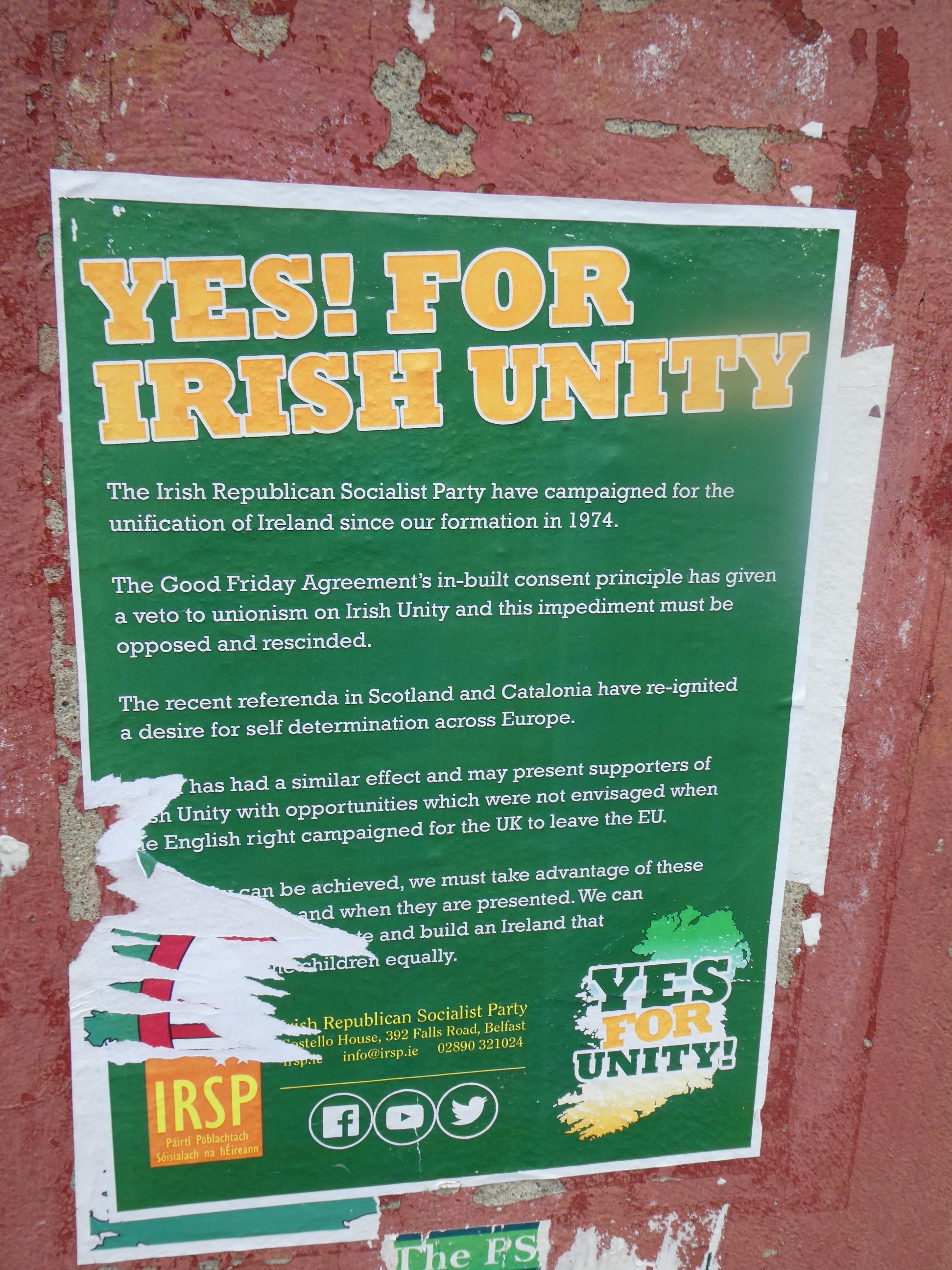

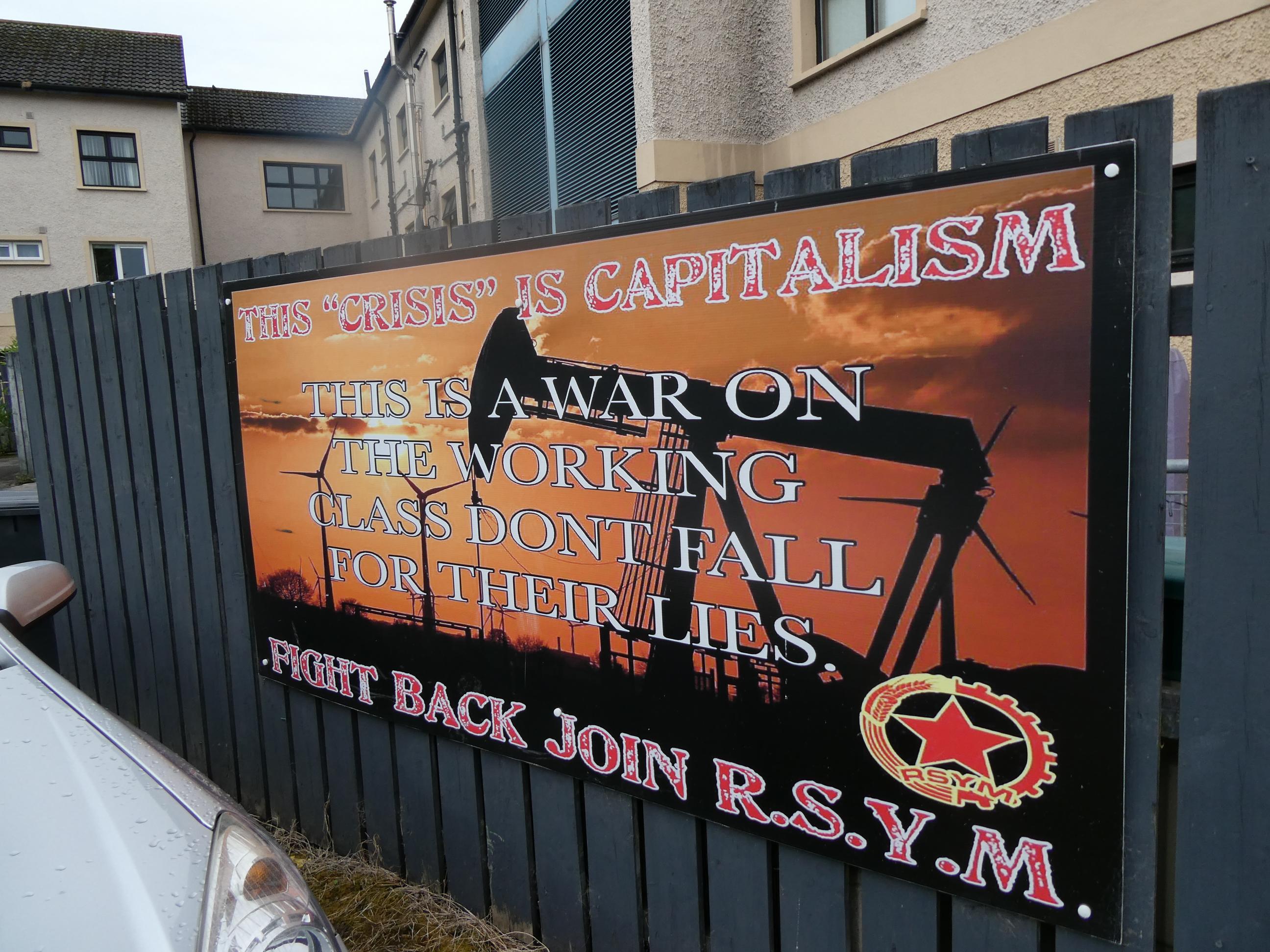

Interspersed with the murals are posters and placards with political messages. It’s very obvious that feelings remain strong here, and this community is still agitating for a united Irish republic. Political parties and action groups continue to hold public meetings and call for action. Volunteers are still sought to join these groups. The IRA and its political wing, Sinn Fein, are supported here.

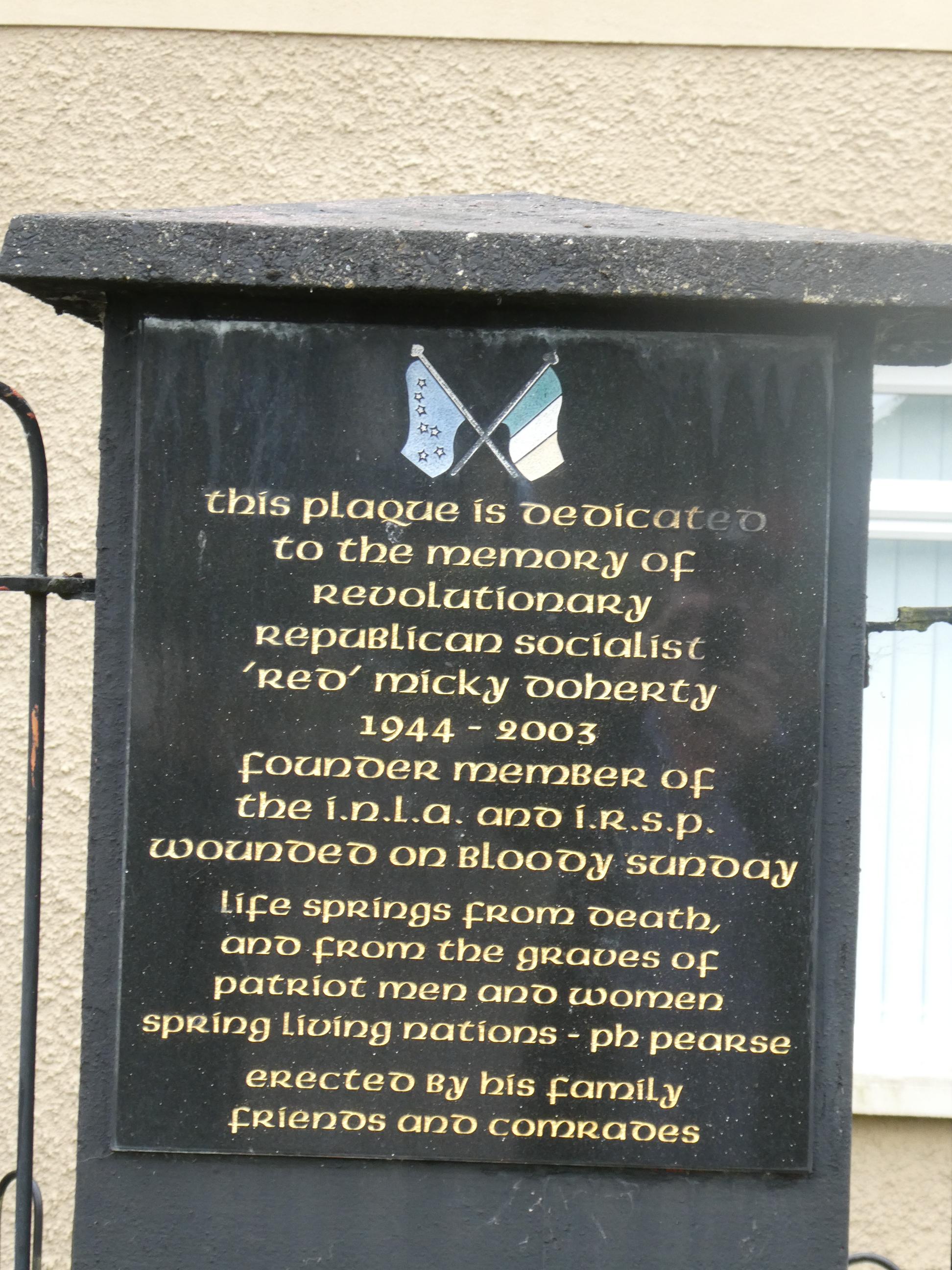

In some places where catholics were killed in the violence, plaques or posters have been placed to commemorate them and remind passers by how their lives ended.

In the centre of the road dividing Bogside from the rest of the city are monuments related to The Troubles. One is erected to remember those who lost their lives in the Bogside violence on Bloody Sunday, 30 January 1972. Another is to remember the ten republican political prisoners who went on a hunger strike in 1981 in H-block of Long Kesh prison to protest their treatment as common criminals. All of them died. It just makes you feel very sad when you stand before these murals and these monuments. I asked myself if all of this could have possibly been avoided. I don’t have the answers.

The Free Derry wall has been left standing. It’s in the centre of a busy road, where it must be seen by countless Bogside residents every day. The tricolour orange flag of Ireland flies proudly above it.

We left Bogside and walked up a path to the city walls. The older part of Derry is completely enclosed by the walls. The walls were built in the 1610s. Around that time, British settlers moved in to colonise the area and benefit from its agricultural resources. They forced the native Irish population out of what had previously been their home turf and onto undesirable land. In order to protect their newly gained territory from the Irish trying to take it back, the British erected strong walls and mounted cannons along their length. As we walked along the top of the wall, we passed several protestant churches located within the old city. There were no catholic churches, however, as catholics were never allowed to live within the city’s walls.

We left Derry by 11am and headed south west towards Sligo. It rained from time to time. The country we passed through was mainly flat, fertile green farmland, but when we drove through Donegal the terrain changed for a time. It was wilder country and reminded me a great deal of some of the wonderful Scottish highlands I loved.

We found a parking spot in Sligo and stopped for lunch. Sligo happens to be the surname of one of the headmasters I worked for at Ivanhoe. He was an arrogant man and I never liked him as a person or working for him. I don’t know if he had any personal connection to the town of Sligo, but, needless to say, I’m glad we didn’t stay long.

In late afternoon we arrived in Galway. The rain had stopped and occasionally we spied a patch of blue in the sky. Marg has been waiting to get back to Galway so she could get a Claddagh ring. Claddagh rings symbolise three things – a heart represents love, a crown represents loyalty, and clasped hands represent friendship. We found one she liked. It’s first made as a long ‘stamp’, using a silicon mould, then a jeweller shapes it into a ring. We went to the Claddagh ring shop we saw last time we were here and ordered one. She left the shop very happy. I love Galway for its music. Buskers play up and down the street. I spent some time enjoying the guy playing covers on the corner. He was very, very good. I only had a couple of euro coins for him. I hope he did well today. We met up with Rod and Cornelia and walked around to look at the Lynch window before dinner. Hundreds of years ago, a man named Lynch was Mayor of Galway. His son committed a terrible crime and was sentenced to hang, but no one wanted to be the hangman for fear of falling foul of his father. So Mayor Lynch stepped forward and hanged his own son from the window high up on the stone wall you can see below (to the left of the balloon pic). This is where we get the word ‘lynch’ from. Tomorrow we might have time for a longer look around Galway.