With just one full day in Belfast available to us, we opted for two of the most popular tourist attractions in the city. The first was to do one of Belfast’s famous black cab tours of areas of the city associated with the period of recent history known as The Troubles. And the second was to do the Titanic Experience down near the shipyards where the ill-fated luxury ocean liner was built.

Our first stop on the black cab tour was the Peace Wall in Cupar Way that separates Shankill Road, the area linked to Belfast’s union loyalists (essentially protestants who want Northern Ireland to remain under British control), from Falls Road, the area linked to Belfast’s republicans (essentially catholics who want to be part of Ireland). The peace wall we stopped by is three miles long. Our driver, Liam, handed out some marker pens and encouraged us to find a space and write a message of peace on the wall. I’ve included a message from Marg in my photos, because when I checked the photo of the message I wrote, I noticed, too late, a really obscene message written just below it, and I was not going to have that on my blog. A very high fence along the peace wall is there to limit the amount of projectiles which can be thrown over the wall to the other side.

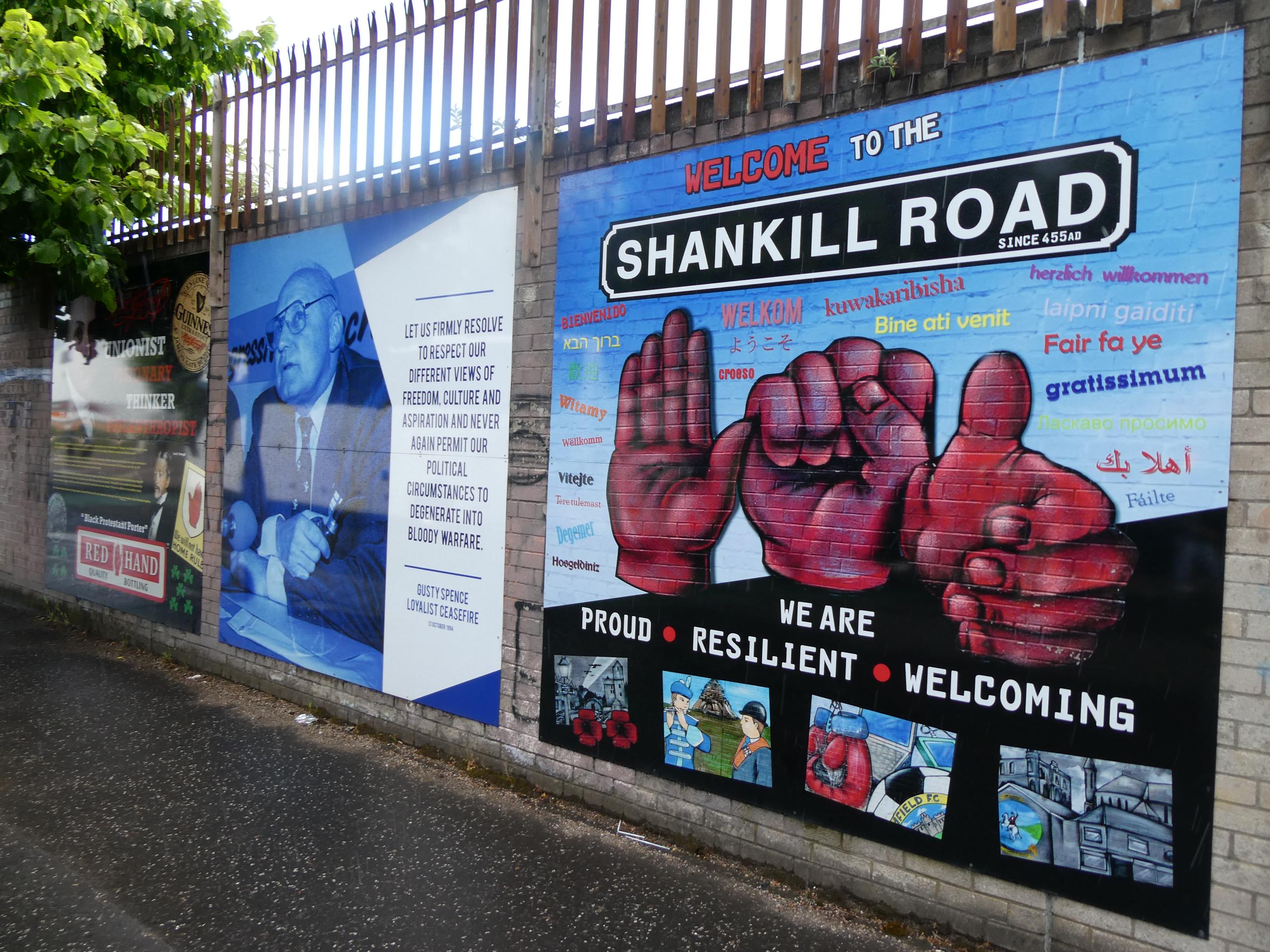

Next we drove down Shankill Road, the protestant area. The people who live on this side of the peace wall are loyal to the British crown and consider themselves part of the United Kingdom. During the thirty years of The Troubles, which lasted from about 1966 until 1998, loyalist groups such as the Ulster Volunteer Force and the Ulster Defence Association were active along Shankill Road. Some were associated with fire bombing a catholic pub, and others with a series of murders of catholics. Shankill Road was also the scene of a number of bombings and killings carried out by the IRA, the catholic Irish Republican Army. Today, there are large murals along Shankill Road outlining murders committed by republicans against loyalists, not only in Belfast, but also in other parts of the world. There are also memorial gardens, like the one we visited, which you can see below. It commemorates protestants who lost their lives during The Troubles, but also contains messages of accusation and hatred. British flags line the street. You can’t miss them. The message is pretty clear. Catholic republicans are not welcome here. It seems there are many loyalists still here with very long memories.

Shankill Road was also the place where an incident occurred that brought The Troubles to an end. In 1993, two IRA members carrying a bomb entered a fish shop there, where a meeting of the loyalist Ulster Defence Association was supposedly happening upstairs. The bomb detonated prematurely, killing one of the bombers and one of the UDA members. It also killed eight protestant civilians, including some children. Many others were wounded. The following week, in a number of revenge attacks, loyalists killed a number of catholic civilians.

In addition to the peace walls that separate the protestant Shankill Road area from the catholic Falls Road area, a number of peace gates on the streets that link them are still locked at 8.30pm every night, with the intention of preventing lingering tensions between the two groups from spilling over into violence again.

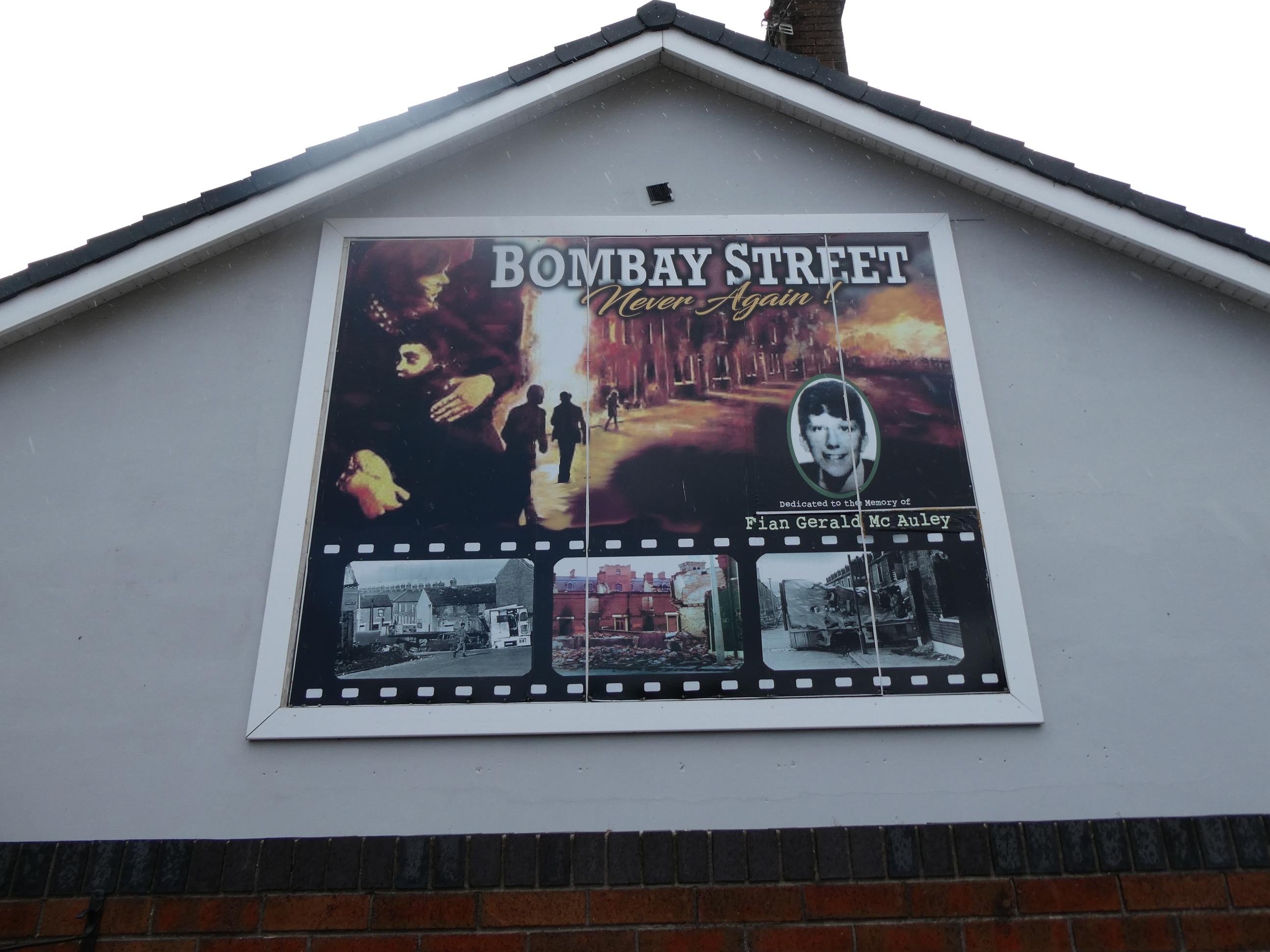

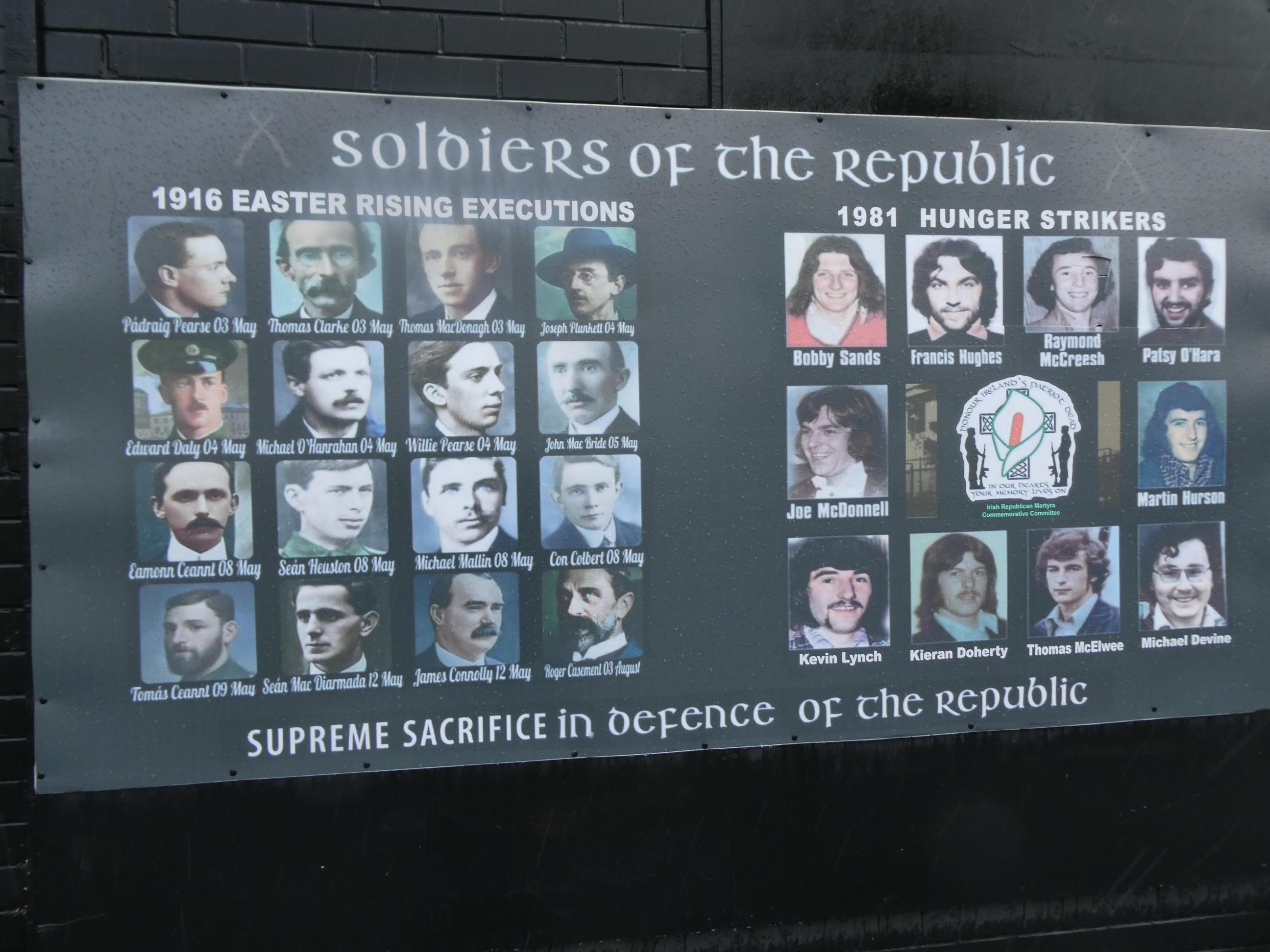

We left Shankill Road and drove into the catholic Falls Road district, where our driver Liam grew up. In the first photo below, you can see the back of the peace wall. It’s bare of murals. You can see it again in one of the last photos in this block, and you will notice that the backs of the houses that abut the wall here have cages built over their doors and windows to provide protection from whatever missiles might be thrown over the wall. We stopped at the Clonard Martyrs Memorial Garden in Bombay Street. The Clonard Monastery is nearby. In 1969, a protestant mob rampaged down Bombay Street, fire bombing each house as they passed. All of the houses in catholic Bombay Street burnt to the ground. A priest from the monastery watched the violence unfold, and anointed a number of those dying around him. He tried to call in the British troops to quell the violence. This memorial garden did not reflect hatred like the one in Shankill Road. Instead, it was a place of reflection and remembrance. Liam pulled a plastic bullet from his coat pocket to show us. He said it was fired by British troops to disperse crowds during The Troubles. I asked him how he got it. He said it hit him. He told me he just got in the way and it struck him in the leg. It was a hard, solid object. I can imagine if it was fired from a gun, it could cause great injury. Liam told us sixteen people had died after being struck by plastic bullets during the conflict. Also on the Falls Road, we stopped at the mural depicting Bobby Sands and his fellow hunger strikers. They began a hunger strike at Maze Prison after the British government removed their special status as political prisoners and began treating them as common criminals. In 1981, Bobby Sands refused food for 66 days, and eventually died of starvation. He was the first of ten hunger strikers to die. Our driver Liam visited one of them, his friend Joe McDonnell, shortly before he also passed away. Liam said it was terrible. Joe was just skin and bones.

We stopped to take photos at one of the peace wall gates. Within minutes of getting out of the cab, heavy, bitterly cold rain began to fall. It didn’t last long, but it gave us a taste of how changeable Belfast’s weather can be. Alongside these gates is what’s known as the international wall. There are murals here linked to Belfast’s sectarian violence, but also others linked to other conflicts around the world or efforts to bring about peace. This gate also closes each night at 8.30pm to prevent loyalists and republicans entering each others’ areas and creating mischief.

The Troubles ended with the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. It led to the formation of a new government for Northern Ireland where both loyalists and republicans are represented and share power. It acknowledged that there are differing views among the people, and that currently the majority wish to remain under British rule. It also stated that if the majority shifts to favouring a united Irish republic in both Ireland and Northern Ireland, then this will be taken into consideration and could lead to a change in Northern Ireland’s status. The agreement committed both sides to resolve their differences peacefully and to lay down their arms. The British soldiers withdrew from Northern Ireland and a number of political prisoners were released. To date, the agreement has been effective in stopping the violence.

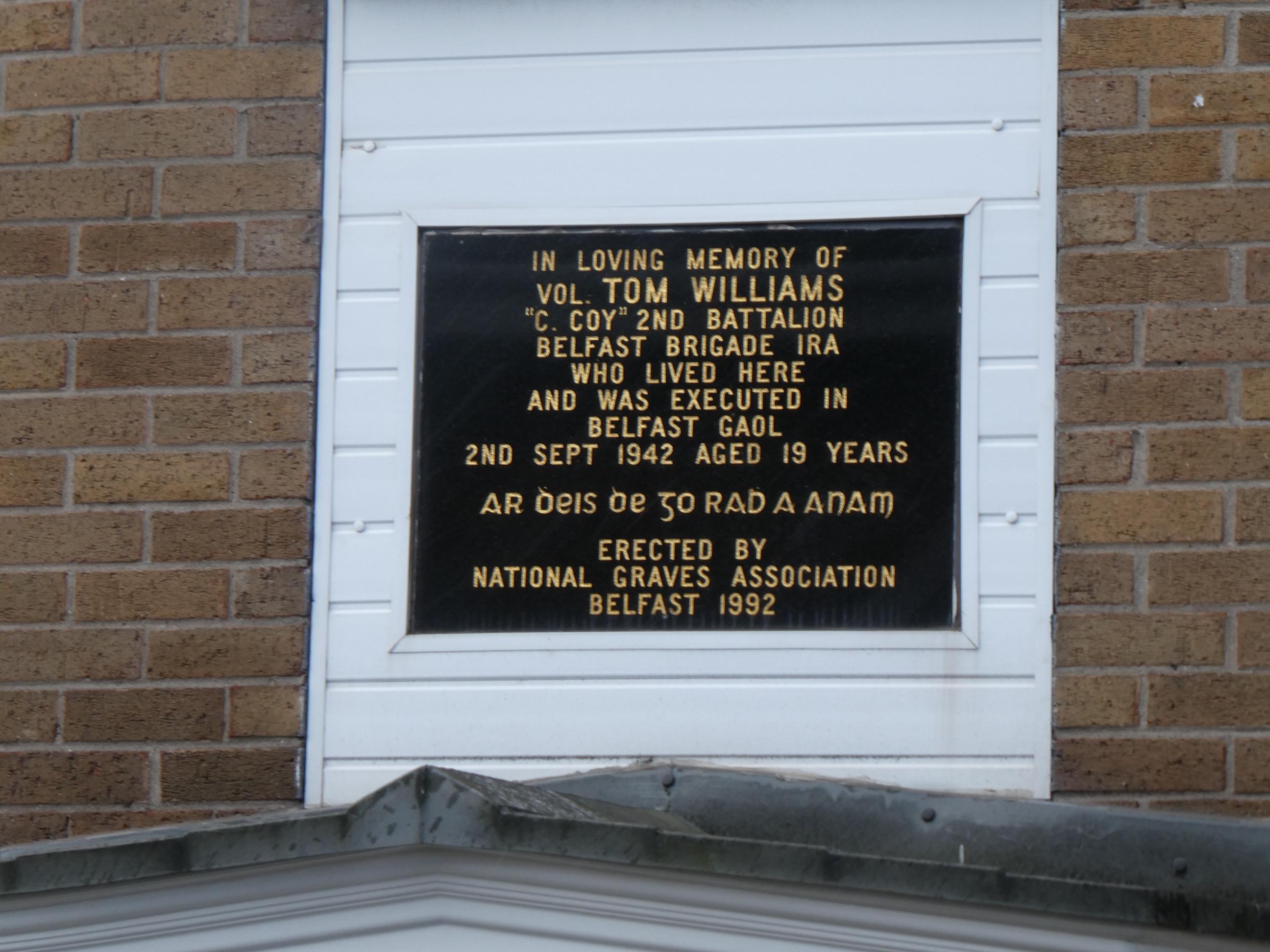

Our black cab tour finished at the gates of Crumlin Road Gaol, a Victorian-era prison that is no longer in service. We were able to take a self-guided tour. For most of its history, it housed criminals, but in later years it also held political prisoners. Seventeen people were hanged for their crimes here, and most of their bodies were interred on the grounds in unmarked graves. The courthouse was immediately across the road. When convicted, criminals would cross through a tunnel beneath the road from the courthouse to the prison. The courthouse was decommissioned not so long ago and has fallen into disrepair. Several forms of transport, used by the British military during The Troubles, are on display in the courtyard. I did not find this prison as dark and miserable as Kilmainham in Dublin, which we visited earlier in the week.

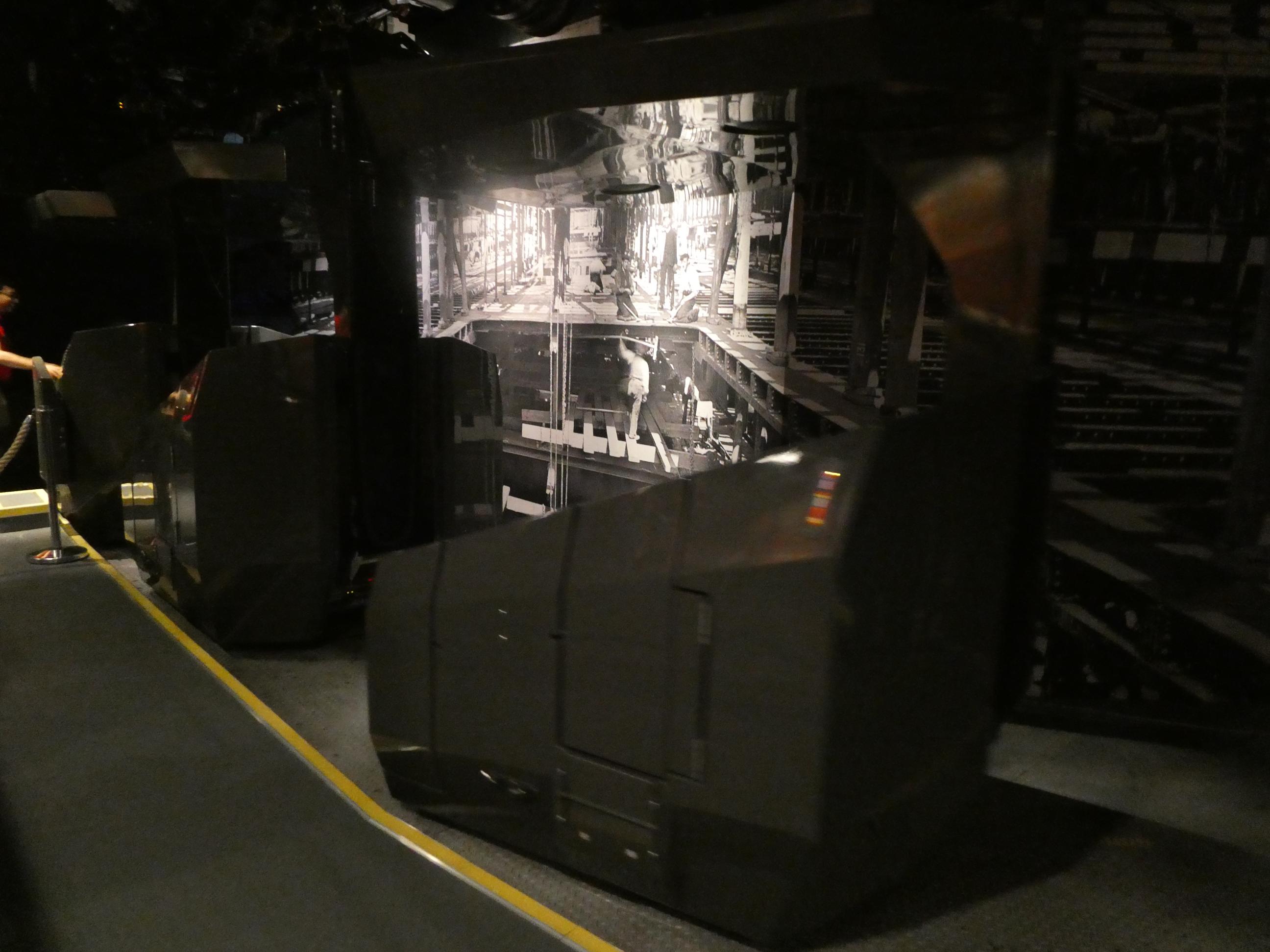

Marg and I caught an Uber from the prison to the former shipyards near the marina where the Titanic was built. Rod and Cornelia walked there from the prison. The Titanic Experience is housed in an ultra modern structure, that allows you to follow the Titanic’s story from the industries that were thriving in Belfast at the beginning of the 1900s, including shipbuilding, through the construction and fitting out of the great ship, to its launch and maiden voyage, to the tragic collision with an iceberg in the North Atlantic that led to its sinking and the deaths of many of its passengers. The exhibition focuses on a range of different people who were on the voyage. We were able to witness the public response to the Titanic’s sinking and learn about the safety measures that came out of the inquiry that followed. We followed Ballard’s quest that eventually led to his team discovering the Titanic on the ocean floor. Probably the highlight of the tour was the ride, where we were taken through different stages of the construction so we could see it as the workers who built the ship would have seen it. It was a really interesting experience, and one of the best museums I’ve seen. We spent a couple of hours there.

In the dry dock about a couple of hundred metres away was the Nomadic, smaller sister ship of Titanic, and the last remaining ship of the White Star Line. Nomadic is no longer in service, nor is the dry dock. Nomadic was a tender ship. It’s purpose was to relay passengers and goods between a much larger ship and the shore. Often the larger ship could not sail in shallow harbours and had to wait outside while the tender ferried people back and forth. One of the last ports Titanic called in at on its fateful maiden voyage was Cherbourg in France. It dropped anchor some distance off shore while the smaller Nomadic brought passengers and cargo out to the ship. Thankfully the rain held off for most of our walk back to the hotel, though the wind at times was bitterly cold