Before we left Australia, I logged on to the Kilmainham Gaol website to book tickets for a tour on our first full day in Dublin. I learned that they only released tickets about four weeks in advance, and that they were linked to specific timeslots. I also noticed that the available tickets were snapped up very quickly and most time slots were marked ‘Sold Out’. I learned that new tickets were made available immediately after midnight in Dublin, which was 9am in Australia. I got in touch with Rod and told him that if we wanted to book tickets for May 21, we would have to click onto the booking link as soon as it turned 9am on April 23. As we knew tickets would go very quickly, we agreed that I would try for a morning timeslot and Rod for a timeslot after 1pm. We were on speaker phone so we could keep each other updated on our progress. At 9am I got in straight away and noticed that the first available timeslot was 9.45am, so I selected four adults and put the tickets in my shopping cart. I noticed when I logged in that each timeslot initially allowed only 35 tickets, and that the number of available tickets for each timeslot kept reducing before my eyes. ‘I’m in and I’ve got the tickets,’ I told Rod. ‘You won’t need to try for the afternoon.’ By the time I’d added my contact detail info, the time was 9.02am and Rod said, ‘There’s now only 4 tickets still available at 9.45.’ By the time I completed the whole transaction and received my tickets, it was 9.04am and I heard Rod say, ‘All timeslots for the day are now sold out except the final one, and there’s only one ticket still available for that one.’ So, given that all tickets for each day at Kilmainham are presumably snapped up within the first five minutes of going on sale, I think we did very well – and were very lucky.

We took a taxi out to the front gate of Kilmainham. Our taxi driver, Anthony, was a real character. He chatted away all the way to the gaol, giving us lots of tips for things to do in Dublin and also giving us an insight into his family life and the fortunes of each of his three kids. He told us he’d lived in Melbourne for 12 years while he managed the Knox depot of Ventura busline.

The prison was a real eye opener. It was opened in the 1700s, but essentially was a Victorian era structure that was one of the first ‘reform’ prisons, where the aim was to rehabilitate prisoners so that they could return to society and never re-offend. It’s unlikely that actually happened very often. 90 percent of the prisoners at Kilmainham were convicted criminals. Some were murderers and deserved to be there, but many were people convicted of petty crimes like stealing food, loitering or begging – because they were starving. During the 1840s, Ireland suffered the terrible potato famine and over one million people died from starvation and related illnesses. They were desperate to find food for their families and committed very minor crimes as they fought to survive. Some were incarcerated with hard labour, which must have been very hard, but few who went to prison died because they were all fed better than they probably would have been on the outside. The youngest recorded prisoner was a three year old boy convicted of begging. The remaining 10 percent of prisoners were political prisoners, most of them incarcerated by the British lawmakers because of their struggles to support the cause of Irish independence. For a time, Irish republicans did not win over the hearts of a good deal of the Irish people. Many did not support their rebel cause because the skirmishes with British troops only brought hardship, destruction and food shortages. Everything changed on Easter Monday, 1916, when a group of Irish republicans declared the formation of an Irish republic and holed up in the GPO building in Dublin and stayed there for several days while the British tried to quell their uprising. Eventually they were captured, tried and sentenced to death. They were sent to Kilmainham Gaol, where the death sentences were carried out by firing squad. The brutality of English law was unjustified and unacceptable to the people of Ireland. Whereas many had not actively supported the republican cause prior to the Easter Uprising, they now committed themselves to fully supporting the rebel cause. It was the turning point that eventually led to the formation of the Irish Free State in 1922. The fourteen courageous prisoners who were executed by the British became Irish national heroes. I was quite moved by their story and the visit to Kilmainham. I’m so glad we got those tickets, because now I feel I’ll appreciate and understand many things I see and hear in Ireland much better than I otherwise would have.

As I mentioned earlier, our taxi driver, Anthony, had given us a few tourist tips for our time in Dublin, one of which was a shortcut we should take through the grounds of the Irish Museum of Modern Art. It had been cool when we entered the gaol, but it was warm and sunny when we emerged, and we enjoyed the walk through the leafy green park and the art museum grounds that Anthony recommended.

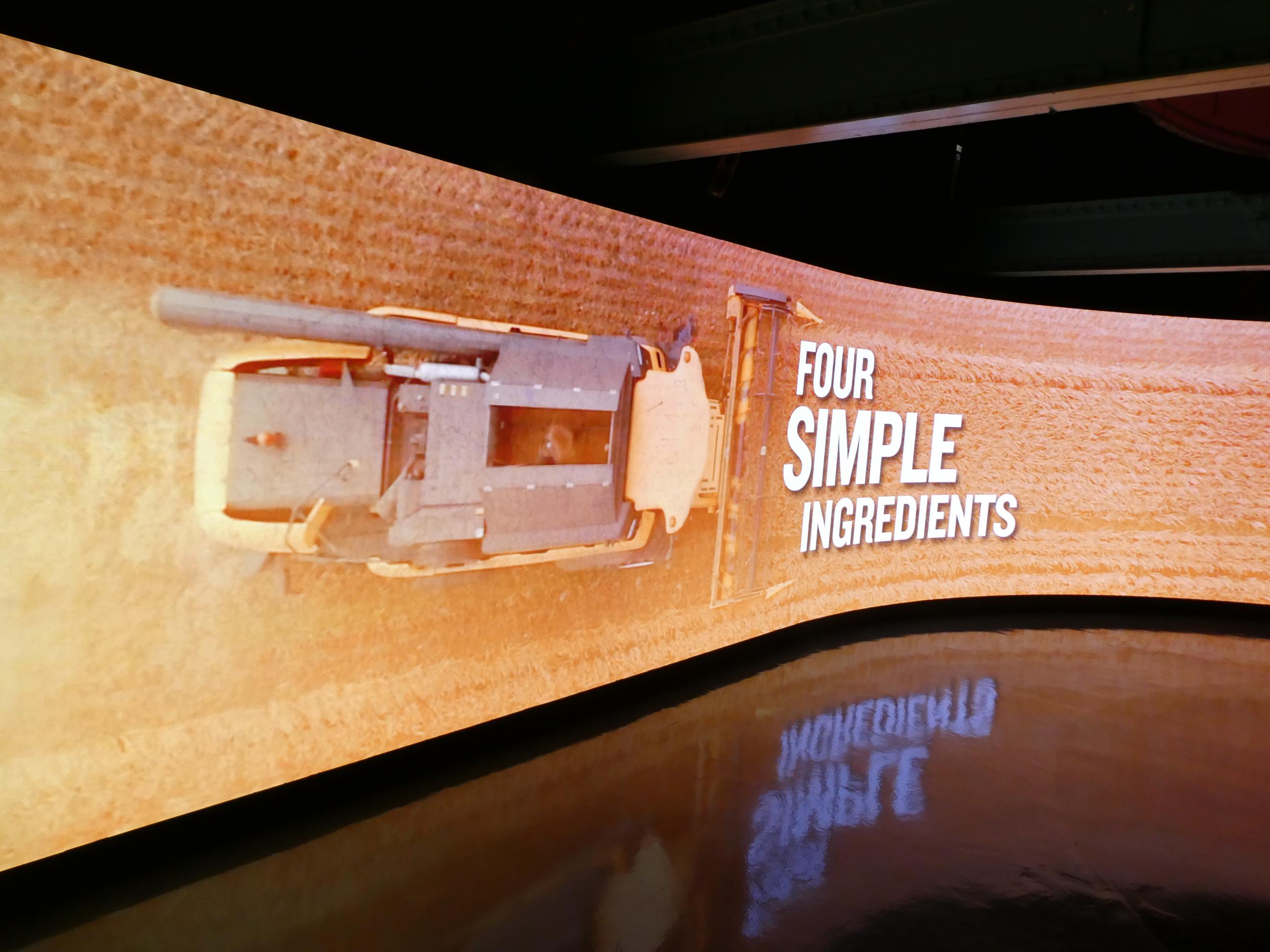

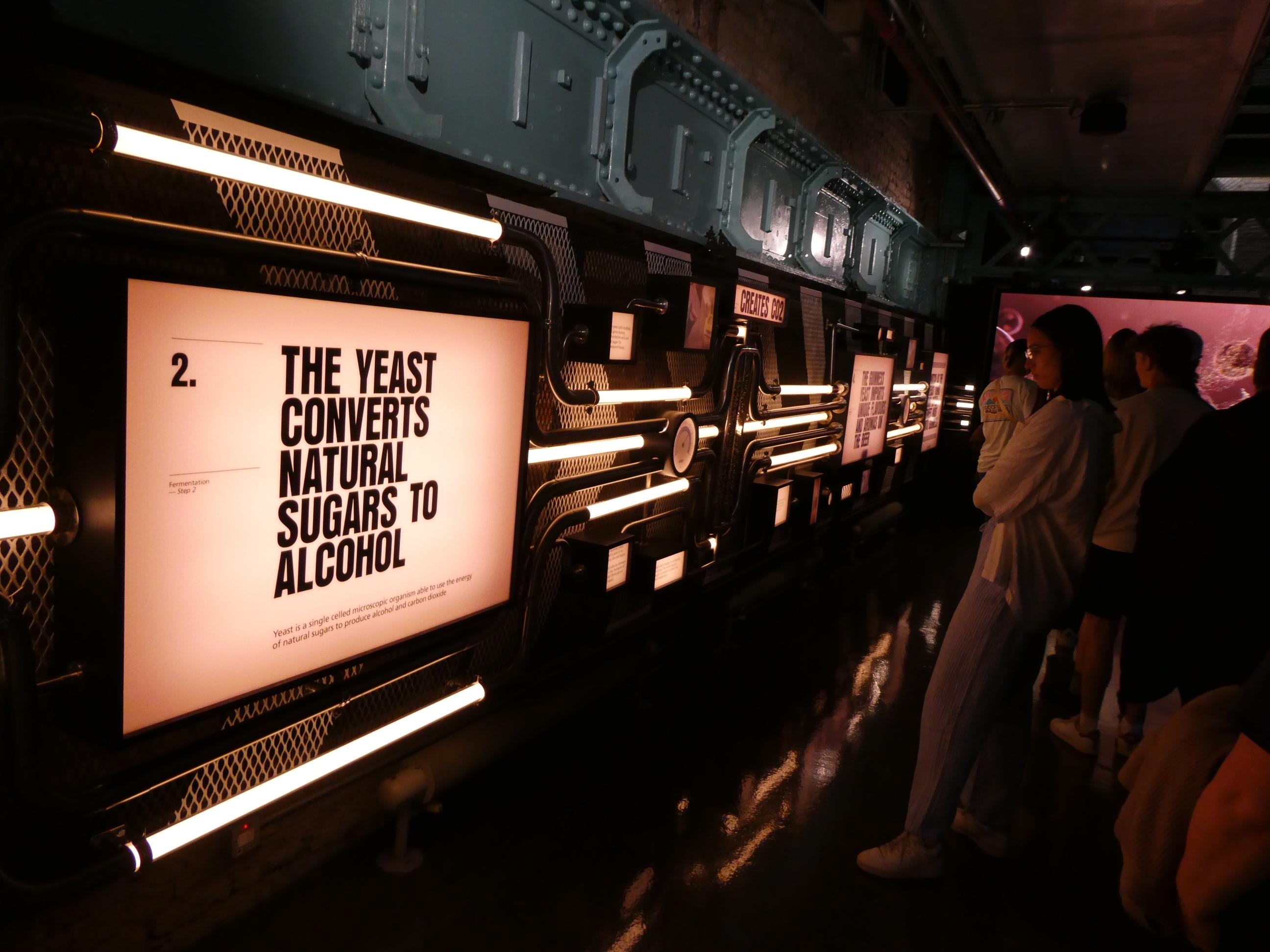

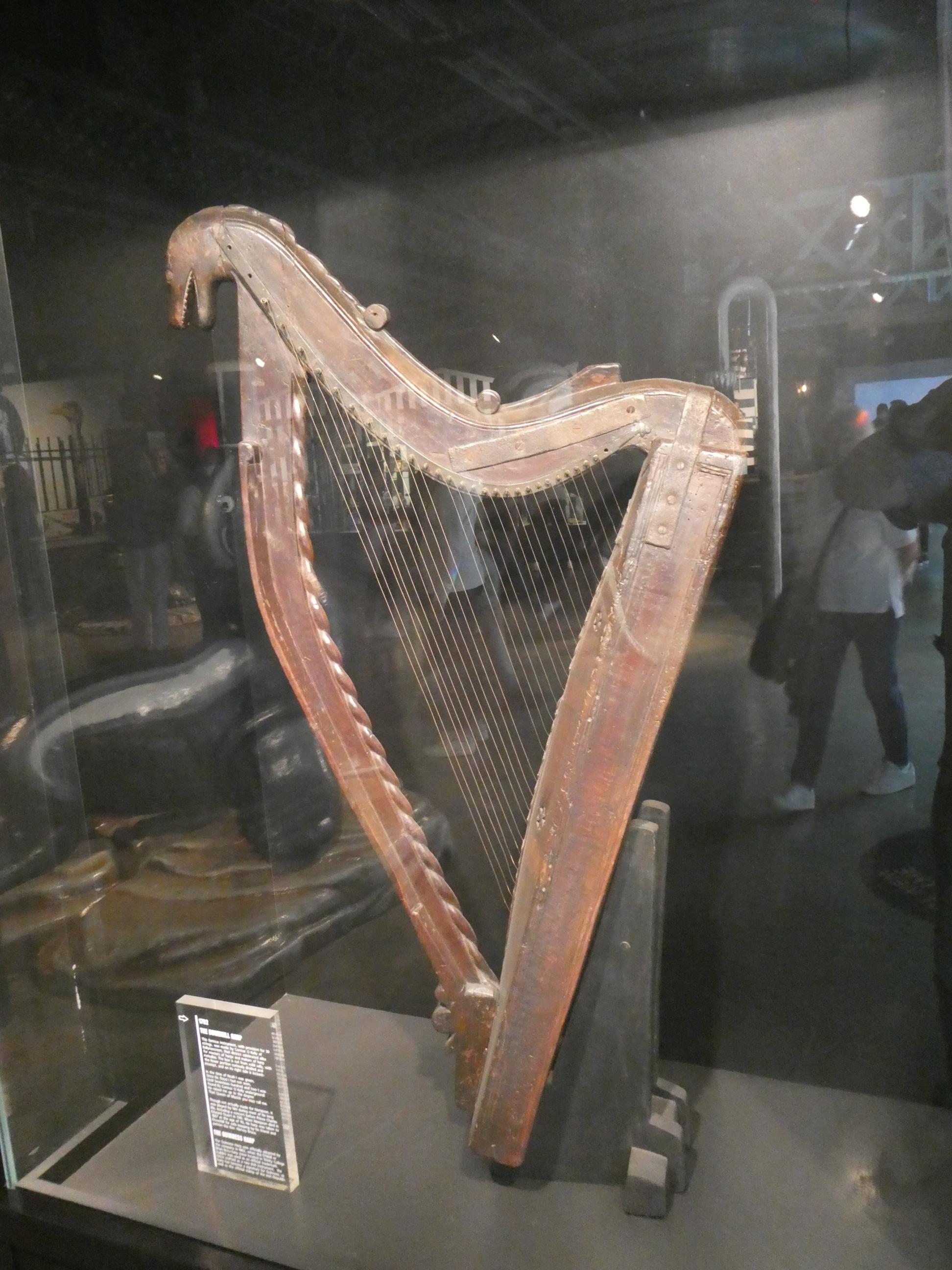

We arrived at the Guinness Storehouse and joined a long queue waiting under the warm sun. Although Marg and I had been here six years earlier, we had been on a bus tour and were given a time to be back on the bus. Our tour director advised those of us who wanted to learn to pour a Guinness to get straight up to the fourth floor and make sure we did that first. Then to head up to the Gravity Bar on the top floor for another complimentary drink. Once we’d done that, it was almost time to get back on the bus, meaning that we saw very little of the displays on the first, second and third levels that told the story of Guinness and how it was made. Consequently, I was glad to be back here again, so I could see what I missed out on the first time. And, I was looking forward to pouring another Guinness and enjoying one with my brother. It really is a fantastic experience visiting the storehouse because the factory infrastructure seems to be all around you as you move through it – the pipes, beams, boilers, pumps and so on – but so too are fabulous panels and video screens and interactive information stations and attention grabbing displays. It’s a visual smorgasbord as you move through it, learning all you need to know about the four ingredients needed to make a Guinness and each of the important steps in the manufacturing process. You also get to see how Guinness has been marketed over the years and around the world, including some very, very clever advertising. The one that we liked was the fish on a bicycle ad from 1996.

On the Guinness Academy level, Rod and I each took a turn at pouring a Guinness, and did a pretty good job, I think. The secret is to begin with the glass on a 45 degree angle and pull the tap forward, then straighten the glass as it fills and stop with a few centimetres of space remaining to be filled. The glass needs to sit for at least 70 seconds while the bubbles rise to form a creamy head and the dark beer settles below. Once it has settled, the second pour takes place, with the tap pushed back away from the person pouring it. The end result is a ‘perfect pint’ of Guinness with a thick, creamy head. Just right for drinking. We stopped to eat lunch on the fifth level, then climbed the stairs to the top level Gravity Bar, where Rod and I received a second complimentary pint and Marg and Cornelia had a soft drink, as they aren’t so keen on the taste of Guinness. The bar was pretty crowded, so we downed our drinks quickly while checking out some of the views over Dublin, then headed for the gift shop and the exit.

We had about a twenty minute walk to our next stop, St Patrick’s Cathedral, where we also had a timed ticket. We arrived just minutes before our free tour was due to begin.

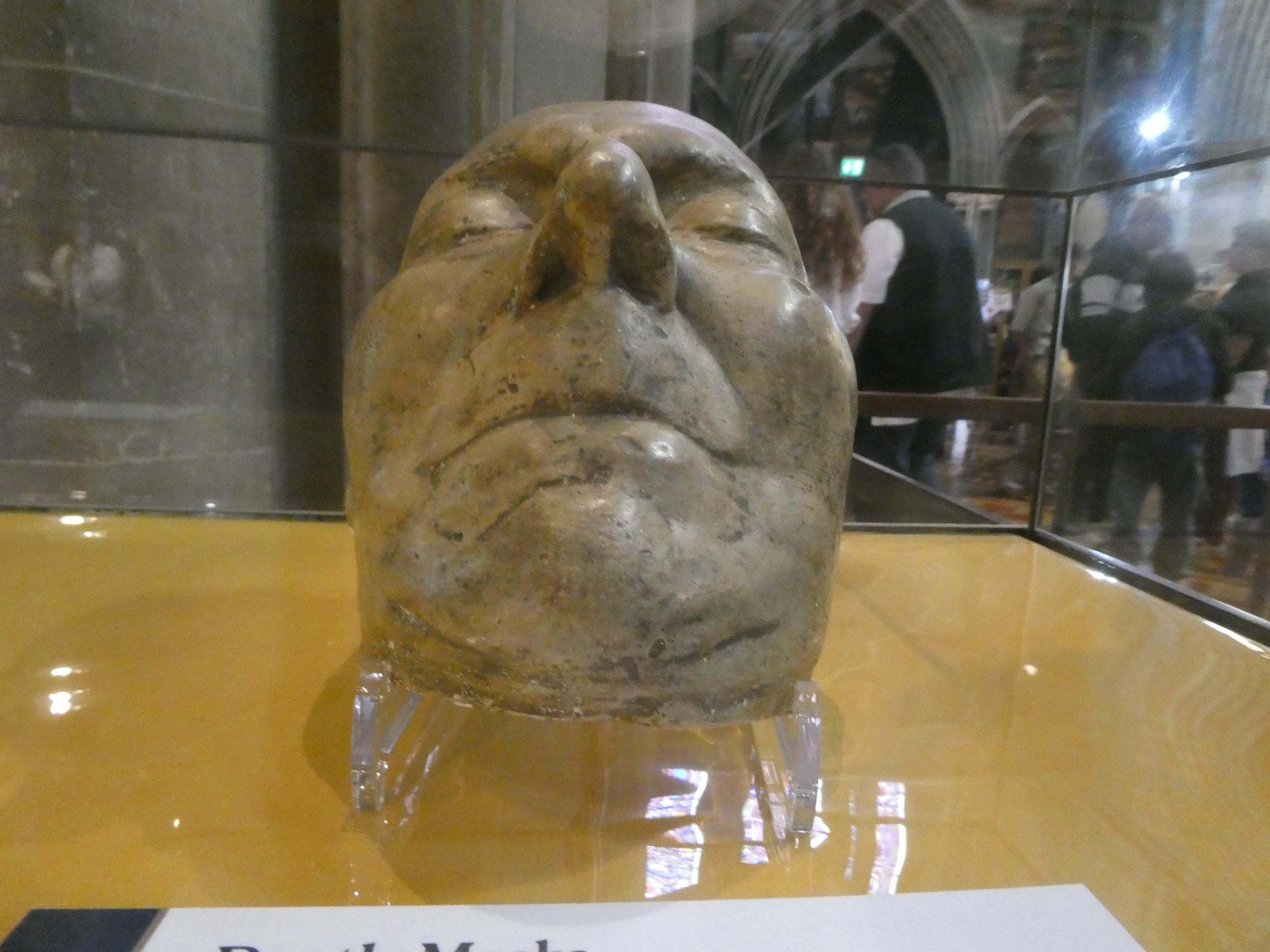

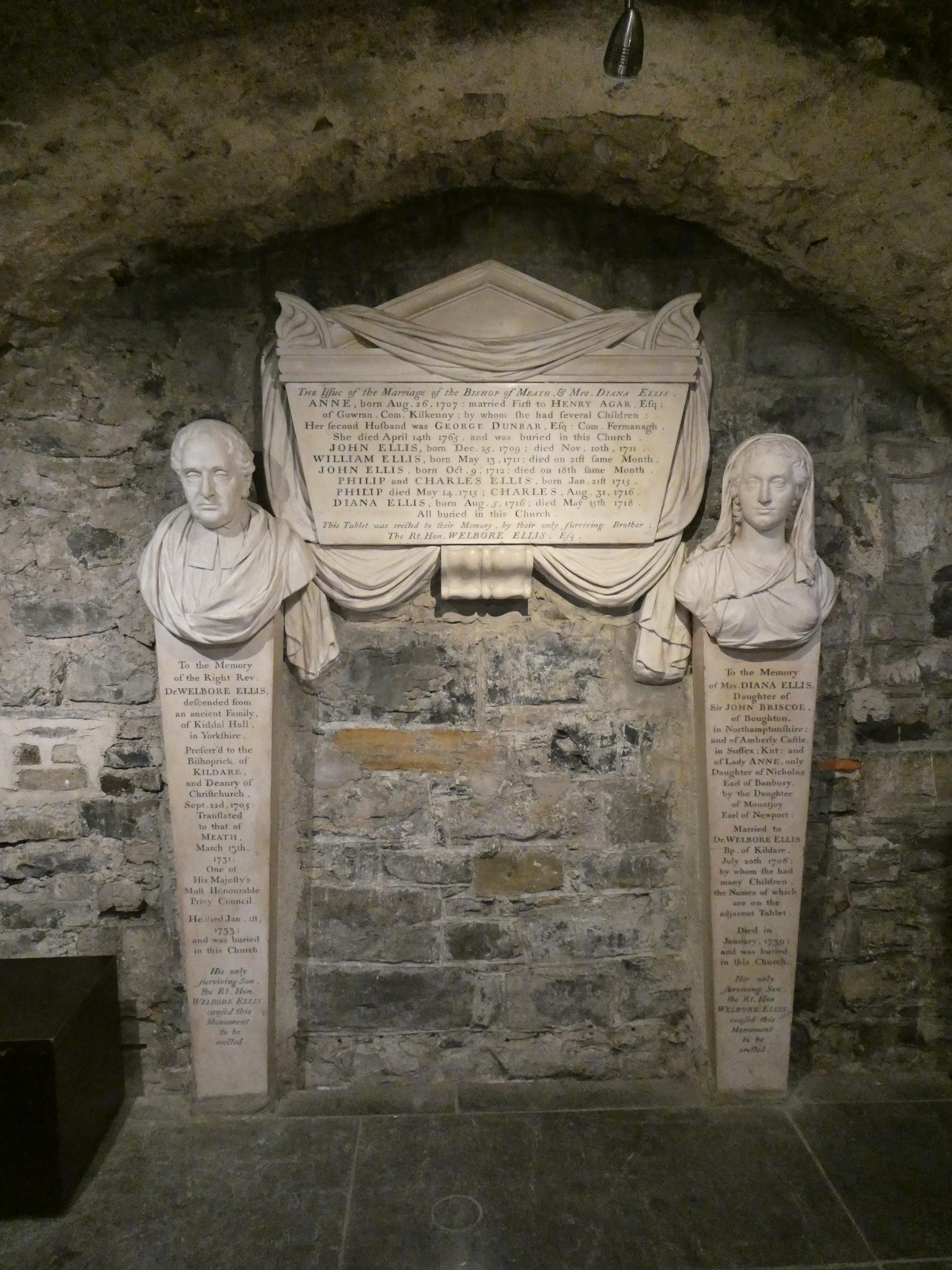

St Patrick’s is Ireland’s largest cathedral. It dates back over 800 years. We joined a free tour with a guide, appropriately named Paddy. He showed us around some of the highlights of the chapel, but interestingly asked us not to ask him too many questions about religion as he didn’t feel he knew enough about it to answer them. And besides, Paddy was baptised as a Roman Catholic, whereas St Patrick’s, which began as a Catholic cathedral, has been a protestant Church of Ireland cathedral, linked to the Anglican church, for hundreds of years. Instead, Paddy was keen to speak of the history of the building and the possible links it had to St Patrick in the 5th century, which can never be proved or disproved. He spoke about Richard Boyle, who arrived almost penniless in Ireland from England, married a wealthy Irish woman, and thus became a wealthy man himself and a prominent figure at St Patrick’s. He erected a huge monument inside the cathedral to honour his wife, her family and their own children. He’s the man behind Boyle’s Law, which I once learned at high school but have now conveniently forgotten. Paddy was in his element regaling us with stories about Jonathan Swift, author of ‘Gulliver’s Travels’ and a well-known satirist, but also an influential dean of St Patrick’s. He showed us some of the objects linked to Swift that showed different sides of his nature, finishing with a plaster cast of his skull and a death mask.

Just a short distance from St Patrick’s we visited another Church of Ireland protestant cathedral. This was Christ Church Cathedral, which is even older than St Patrick’s. We’d had a long day already, so we opted not to take a guided tour here and, instead, just have a look around ourselves. The most unusual item I saw in this cathedral was the 800-year old mummified heart of Saint Laurence O’Toole, a former bishop of the cathedral, enclosed in a heart shaped box. As I stood before it, puzzling over its significance, a young woman came and knelt before it in prayer, so it clearly an important religious icon. I learned later that it was stolen by a thief in 2012 and found in good order six years later and returned to the cathedral. I also liked some of the artefacts in the crypt, including the Tudor costumes, the Irish copy of the Magna Carta handwritten in a bound book, and the petrified cat and rat, which were discovered in the organ during the 1800s. Marg was captivated by the Chinese peonies in the garden.

We stopped by the famous statue of Molly Malone. You might know the song about Molly selling cockles and mussels from her cart. When she died they said she became a ghost and haunted the streets of Dublin. As far as I’m aware, Molly was a fictional character. We crossed over the Ha’penny Bridge, which was the first footbridge built in Dublin over the River Liffey. It’s name refers to the toll of half a penny that it cost to use the bridge. From there we walked back to our hotel.

Wow. What a busy day you all had. All so informative and interesting Garry. Hope you haven’t heard any fire sirens on this trip so far.

LikeLiked by 1 person