We hadn’t planned anything for today, figuring we would be in Shetland for a week and we might need a quiet day to catch our breath after what had been a very busy time on the Scottish mainland. So we slept in and didn’t wander down into Commercial St, Lerwick until after 9.30 am. We expected to find a few breakfast places open, but about the first 4 or 5 places were all closed. Eventually we came to The Dowry, where we’d eaten last night. They were serving breakfast, but not before 10 am. It was interesting that Lerwick begins serving breakfast at a time when some Australian places finish serving breakfast.

This morning we woke to blue skies and sunshine. There was a bit of a chill in the air, but the sunshine was amazing. It brought out the colours in the stones of the buildings that had looked quite dull yesterday. I thought it might be a good idea to take new photos of some of the places I’d shot yesterday because the sunlight would give them all a real boost. We walked down some new lanes, knowing they would bring us to Commercial St a little quicker than going along Church Rd, like we did yesterday. Some of the lanes are quite steep, but there are so many of them that you can probably take a chance with any of them and you’ll get to where you want to go in the shortest amount of time.

After breakfast we made our way back to our apartment, stopping first in a few craft shops. I wanted to find a hand-knitted beanie made of Shetland wool that I could identify with. It’s probably not a large amount, maybe around 10% of my overall makeup, but I’m very proud of the Shetland DNA I have in my veins. We found a great little place where a lady named Dee helped us choose some hand-knitted goods. Each was tagged with the name of the knitter, who would be paid for the goods Dee sold. I bought a couple of beanies and Marg found some other stuff too, so Dee was very happy that we were contributing to the Shetland economy. She told us more than once how important this was.

I’m a life member of the Shetland Family History Society. It’s all run by volunteers, mostly retirees. They do a wonderful job researching old documents, compiling census data, recording gravestone inscriptions and gathering the old stories of Shetland’s past. Their offices are down by the harbour, opposite the place where the ferry docks.

The SFHS offices are only open between 2 and 4 pm on weekdays, so I took the opportunity to walk down there and hope they could see me. I rang the bell right on two o’clock, and a lovely lady named Elizabeth showed me in. The office consisted of a desk with a computer, a large photocopier, and a couple of walls stacked with shelves full of documents in plastic folders.

I explained my family connection to Elizabeth and she brought up the people in my family tree on screen immediately. I explained to her that I already had all that info, and that, if she didn’t mind, I really was interested in talking about what their lives might have been like. She liked this, as she turned out to be quite a good storyteller, so for the next hour I asked her questions and listened to her stories about Shetland’s people from the past.

I was really keen to explore why the Johnson family was recorded as living at numbers 3, 4, 5 and 11 Burns Lane over a period of at least 47 years. I have this data from the census, which was recorded every ten years. I thought they might have had the one lodging all that time and that the numbers in the laneway just changed occasionally. But Elizabeth told me I was wrong. Lerwick had many narrow lanes running up the hill from Commercial St.

Elizabeth said that each lane had up to 200 dwellings opening up from it. She said the dwellings were very small and that the majority of them would have only been one, and sometimes two, rooms. They were owned by wealthy landlords. The tenants basically had to work for the landlords. The relationship between landlords and tenants was known as the Truck system, a form of urban bondage. As part of the rent, the men had to go out to sea in small boats with the cod fleets and fish for the landlords, and the women who stayed at home would have to knit for the landlords. The fish would be given to the landlord who sold it for a handsome profit, but paid only a small amount to the poor fisherman/tenant, who was then required to purchase all his goods exclusively from the landlord. So often no money changed hands for the poor tenants’ labours, only goods and a roof over their heads, and the poor tenants were forever in debt to their landlords. Elizabeth thought that my family’s addresses of 3, 4, 5 and 11 Burns Lane probably were linked to forced moves because they couldn’t keep pace with the landlord’s demands. She suspected that my family were really poor.

I asked Elizabeth about marriages during the 1800s on Shetland. Would it be highly likely that people from different parts of the islands would meet and marry, or was it more likely that people would only marry within their own areas. She told me that no one in Shetland lived more than five miles from the sea, so the only form of transport in Victorian-era Shetland was boats. Some people lived away from the sea, but few of them were farmers. There were no roads across the islands, only tracks, and if people wanted to travel from one place to another on foot, it would often take two days. They would often be carrying large baskets on their backs, for example, filled with dried peat, finished knitwear or wool, and would stay in halfway houses overnight to break the journey. When the women approached Lerwick, they would stop just outside the town and replace the protective leather gear on their legs and feet with good shoes, so that they would only be seen in town wearing presentable footwear.

Elizabeth said that everyone in a family had access to a peat bank, and that the whole family, children included, often had a job to do with peat cutting. Then the peat had to be stacked and dried, turned over, stacked and dried again, and eventually carried home to the peat stack. Children in rural parts of Shetland were often required to bring peat to school so it could be burned on the hearth in the classroom. Peat would also be stored in people’s homes so it could be burned during the long, cold winters, when the women would stay inside until spring, constantly knitting.

Today you could pay upwards of $300-400 AUD for a hand knitted Shetland sweater, but Elizabeth told me that when she was a little girl, her granny would send her into one of two stores in Lerwick with hand knitted goods. The storekeeper would dismiss her, saying that he didn’t really want any knitted sweaters at all. She would plead that the rent was due and eventually the shopkeeper would say, ‘All right, I’ll give you 50p for it, and not a penny more.’ Sometimes the price offered was as low as 30 p. And Elizabeth’s granny would have to deduct the price of her materials from that before any profit could be made. But she had no other choice but to accept, because she was always in debt to her landlord.

I thanked them for their time and left them with a small donation, as this is the only funding the society gets. I’ve been using their family history resources for several years now, so I like to support their work.

I was walking slowly back to our accommodation from the family history society when Marg texted to say she and the others were heading down to the post office in Commercial St. I took a few diversions before meeting up with them.

The first was a visit to Fort Charlotte, which was an armed fortification and military barracks at the end of the commercial centre of the town. There’s no entrance fee, no guides, and no gift shop. You can walk in by one gate, take your time having a look at it, and walk out by another. The cannons face out over Bressay Sound. They never fired a shot in anger, but for a time were used to train young military recruits and known to fire cannonballs across the water towards Bressay. Leaving Fort Charlotte, I continued to explore more of the lanes of Lerwick.

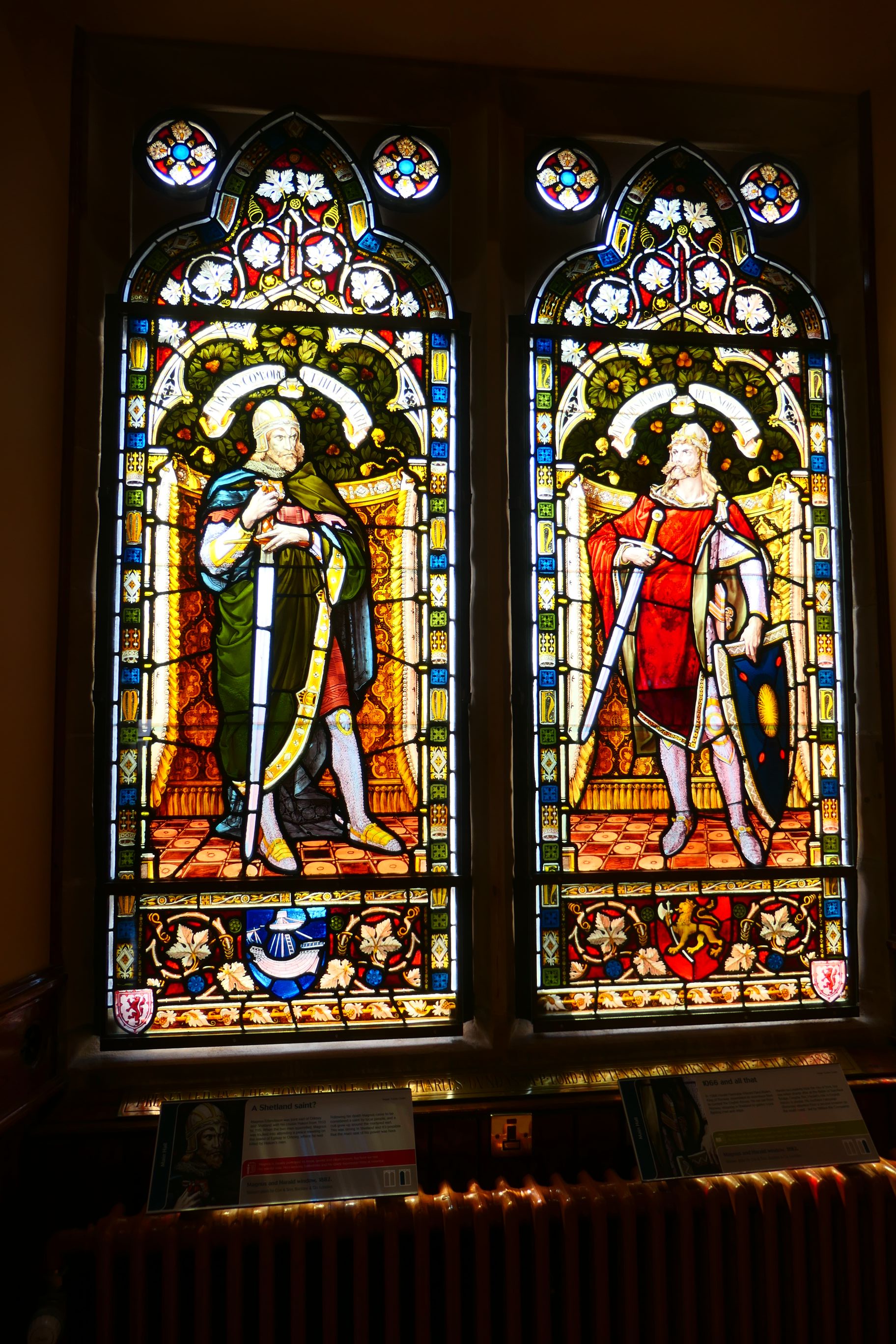

I came upon the town hall, which I’d briefly seen yesterday. It was obvious from the signage that there were places in the building that people could visit – specifically two rooms where very impressive stained glass windows had been installed relatively recently. I spent some time in the meeting room downstairs, but when I got to the main hall upstairs, people were setting it up for a wedding, and the bride and groom and their families were discussing the set up with town hall officials. I excused myself and quickly did a circuit of the windows, then ducked out again.

Tomorrow we have quite a busy day. We’re going on a South Mainland day tour with a man named James Tait. He may even be a relation, as my Shetland third great grandmother was Marion Tait. It promises to be amazing. I think I might need my new Shetland beanie, as we’re going to the southernmost tip of the islands, jutting out into the North Sea. I can’t wait.