We had an early breakfast this morning. A taxi collected us from the guest house before 8 am and drove us a short way to the ferry terminal at Scrabster. We boarded the ferry and left right on time at 8.45 am for the 90 minute, 50 km crossing to Stromness in Orkney. The Northlink ferry is a like a hotel inside with bars, shopping, a dog room and multiple decks. There were plenty of empty seats, so it appears that the passenger numbers weren’t high today. By contrast with yesterday’s blue skies, Thurso was dull and overcast as we pulled away from the terminal this morning.

The journey was quite smooth. There was a small swell, but not enough to concern us. Midway through the voyage we came alongside the first of the Orkney islands on our starboard side. I went out to take a few photos. We were quite sheltered out there, so it wasn’t too bad – a little chilly, but not too much wind. Walking around was when I felt the swell the most, as sometimes the movement of the boat took your body in one direction while your leg was intending to go in another. Once I found my ‘sea legs’ I handled walking around much better.

The large island on our starboard side was Hoy, a name which means ‘high island’ in the Old Norse language. Many place names on Orkney originated from Old Norse, as Orkney was a Viking stronghold for many years. The majority of the people of Orkney can trace their ancestry back to the Vikings.

A famous natural landmark of Hoy is a large stone stack known as The Old Man of Hoy, a column of red sandstone standing 137 metres high. It is situated along the high sea cliffs known as St John’s head and is clearly visible from the ferry as it passes Hoy. Today, however, it was shrouded in mist as we approached. After a time the mist cleared and the Old Man revealed itself.

As the ferry passed the northern end of Hoy and turned to the east, it cruised into calmer waters. Blue skies ahead of us held promise that a brighter day was not too far away. But an unusually heavy cloud hung low over the land, and looked a little menacing at the same time.

A short time later our ferry docked in the sheltered Stromness harbour. Stromness is Orkney’s second largest town. It had been a very relaxing crossing. Our guide for the day, Lorna, was waiting for us. With us in the van for the day were our four American friends, who we’ve seen so much of since we began our rail travels back in Glasgow – Patty and Butch, and Maryanne and Rusty.

Our first stop was at Skara Brae, a neolithic village that was built around 5,000 years ago. In 1850, following a fierce storm, a farmer who lived in a nearby dwelling noticed that the rain and wind had exposed buried stone walls that had long been hidden beneath the sand dunes.

Excavation revealed that he had stumbled across a prehistoric settlement. It contained nine houses built of stone. Each house contained furniture, including beds, storage boxes and something similar to a dressing table on which ornaments were displayed. As the neolithich inhabitants of the village consumed food and created waste, such as bones and shells, it was tossed onto the ground alongside the houses. As the piles of refuse grew, they formed middens, which grew so large that they provided additional insulation and protection for the dwellings they began to enclose. Eventually grass grew over the middens and, therefore, over the dwellings themselves.

At Skara Brae an accurate replica of House No 7 has been reconstructed so that visitors may step inside and experience the interior of a neolithic dwelling. There they will see the family’s beds, seats, storage boxes, fire hearth and dresser. They can marvel at the quality of the stone work and see how the roof has been constructed in order to let the smoke from the fire escape. I developed an appreciation for the engineering skills the neolithic builders must have had to construct such dwellings.

The challenge now for Historic Scotland is to preserve Skara Brae from any further damage caused by weathering, tides, erosion and human use of the site. It could be a delicate task, as, although visitors may carefully walk right up to the edge of the stone walls and in amongst the dwellings, it would only take one or two careless actions to cause serious damage to this archaeological gem, currently considered to be the best preserved neolithic site in all of Europe.

Across the moorland behind Skara Brae, is historic Skaill House, formerly the residence of the Bishop of Orkney.

On a narrow stretch of land which separates sea Loch Stenness from freshwater Loch Harray, we visited the Standing Stones of Stenness. The ancient neolithic monument consists of four large upright stones in a circle that once held twelve stones. The largest stone stands about six metres above the ground. Another three metres is buried below the surface. A large cooking hearth was unearthed in the centre of the former circle. The standing stones date back to the same period, 5000 years ago, as the neolithic dwellings at Skara Brae. A large burial mound stands nearby. Not a great deal is known about the way these stones were used by the people who erected them, but perhaps they were used for a ritual that celebrated their harvests or maybe an event like midsummer.

For quite some time the stones have been attracting tourists, and this hasn’t always pleased the locals. While we were there a large group of cyclists from a cruise ship was visiting the stones. Not all of them were skilled cyclists, and some of them were obstructing cars on the narrow road that runs alongside the stones. In an area that’s quite busy with tour group buses and vans and motor homes, courtesy and patience are required on the road, but while we were there one taxi driver had had enough of a group of selfish, or perhaps incompetent, cyclists blocking his passage, and he gave them a sustained barrage from his horn as he came up behind them. I guess they got the message loud and clear, as they moved out of his way and eventually he got past them and went on his way. Many years ago the farmer who owned the land was fed up with tourists visiting the stones and decided to put an end to it. He drilled some holes in one of the stones where he intended to insert some sticks of explosive. Thankfully someone learned of his plan and talked him out of it before he blew the stones to smithereens. Visitors can still see the holes that he drilled.

During both WWI and WWII, the large harbour known as Scapa Flow was the base for the British Royal Navy. Military authorities wanted to ensure the fleet was safe from enemy attack, so they tried to seal off passages that could be used to enter the harbour by acquiring old ships and deliberately sinking them between the land and small islands, making navigation impossible. The wrecks of some of these sunken ships are still visible above the waterline today.

Just weeks into WWII, a German U boat managed to make its way between the sunken ships and enter Scapa Flow. It torpedoed a British naval ship, the HMS Royal Oak. The ship sank within twelve minutes, and 833 lives were lost. Over 100 of them were between the ages of 15 and 18. First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, ordered that four barriers should be built. These are long causeways made of stone and large concrete blocks that limited access to Scapa Flow. The Churchill Barriers, as they are known, are still in use today. They were built by Italian Prisoners of War, who were captured in North Africa and brought to Orkney.

Although the use of Italian POWs to construct barriers used in the war effort probably contravened international conventions about the work they could be required to do, the Italians were treated well during their time on Orkney. They were given two Nissen huts and permitted to use them to build a chapel for their own use.

The interior of the Italian Chapel is quite unique. At first appearance, it replicates many of the things you might expect to find in an Italian church from the Renaissance era. But a closer look reveals the truth of its construction. The POWs used anything they could scavenge to build it. For example, some of the decorative ironwork used scrap metal from the sunken wrecks. The lanterns hanging from the ceiling were fashioned from used bully beef tins. The tiles were painted on the walls, but appear at first glance to be actual ceramic tiles. The pews were made from old ships’ timbers. The Madonna above the altar was based on a small religious object one POW had carried in his pocket. The statue of St George slaying the dragon was made from cement and barbed wire. The chapel is still used for services and marriages today.

The chapel is really a remarkable example of achievement and ingenuity, given the Italians’ status as prisoners of war and the limited materials available to them. It endures as a symbol of the friendship that exists to this day between Italy and the people of Orkney.

We drove into the main town, Kirkwall, passing the Highland Park Distillery en route. After lunch we visited St Magnus Cathedral. The cathedral was begun in the twelfth century and took almost 300 years to complete. It was built to honour the memory of St Magnus, the Earl of Orkney, a devout Christian whose murder had been ordered by his cousin and rival Hakon. After his death a number of miracles were attributed to him. His nephew Rognvald began the construction of the cathedral in his uncle’s honour. During restoration work in the 1800s, human bones were discovered in a cavity concealed in a stone pillar. The skull had been fractured in a way consistent with a heavy blow from an instrument. The wound was in the same position where Magnus was reportedly struck. It is believed these are the bones of St Magnus and they are now securely interred in the stone pillar where they were found. A cross on the stone marks the spot.

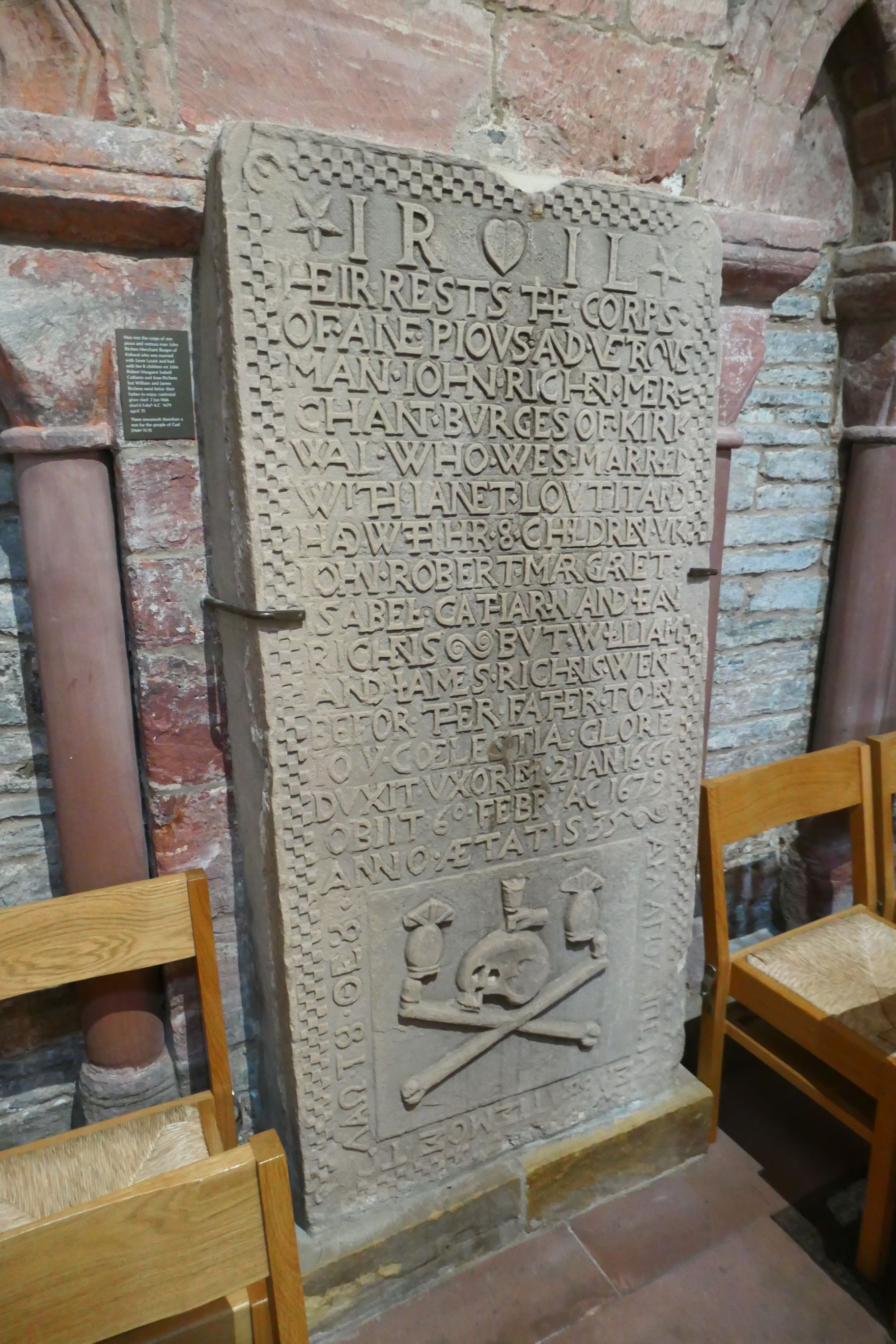

A number of intricately carved memorials from the 1600s line the walls of the cathedral. Many of them bear symbols of death like the skull and cross bones. A memorial with a ship’s bell commemorates those who lost their lives on the Royal Oak. Another memorial commemorates Orcadian Arctic explorer John Rae, who discovered the circumstances behind what happened to the missing Franklin expedition to the North West Passage. Pillars near the entrance to the cathedral lean at a slight angle. The encroaching sea had weakened the ground near the original construction and some pillars had begun subsiding into the ground, so new pillars were constructed to support the structure. A close look reveals two pillars with a slight lean.

Our final visit was to the Ring of Brodgar, a more complete neolithic stone circle, also located on the isthmus between Lochs Stenness and Harray, where we had earlier visited the Stones of Stenness. Thirty-six of the original sixty stones still stand today, surrounded by a large moat that, it has been estimated, took 80,000 man hours to excavate. Large burial mounds are nearby. The ring also dates to neolithic times, 5000 years ago. As with the other standing stones, its exact purpose is not known, although it is believed to have been used in rituals and gatherings. The interior of the circle has never been excavated by archaeologists.

I actually like the idea that there is still an element of mystery surrounding some of the ancient sites on Orkney. I guess we’ll never know the full stories behind them, but I feel grateful to have had the chance to stand alongside them and ponder what might have happened.

On the ferry journey back to Thurso I went outside for one last look at the Old Man of Hoy. There was still a bit of mist around and it took a while before I could get a clearer shot. I guess the mistiness surrounding the stone stack was fitting, giving it a slight air of mystery, just like the standing stones and neolithic dwellings. Orkney seems to be that sort of place. It had been one of the most memorable days of our whole trip and one that I won’t ever forget.

In the evening we dined at Ynot Bar and Grill with Lynn and Don from Canada. They’re also travelling with McKinlay Kidd on the same trip as us, but one day behind. Whenever we stay in a place for two nights, we see them on the second day. Dinner took a long time to be served, but the company was enjoyable so we were happy to wait. When we walked back to the guest house it was still light, even though it was almost 10 pm.